China’s Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law: A warning to the world

Despite its title, the new Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law goes far beyond countering sanctions imposed by other states. It allows for countermeasures against a wide range of actors and actions that China perceives as harming its interests. This brings new risks for political representatives, businesses, NGOs, research institutions and scholars alike, say Helena Legarda and Katja Drinhausen.

The new Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (AFSL) passed by the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress on June 10 is a signal to the rest of the world of what China is willing to do to protect its interests and preserve the stability of its political system. Official sources have framed it as a self-defense mechanism that allows China to counteract foreign sanctions, but the law is in fact much more expansive.

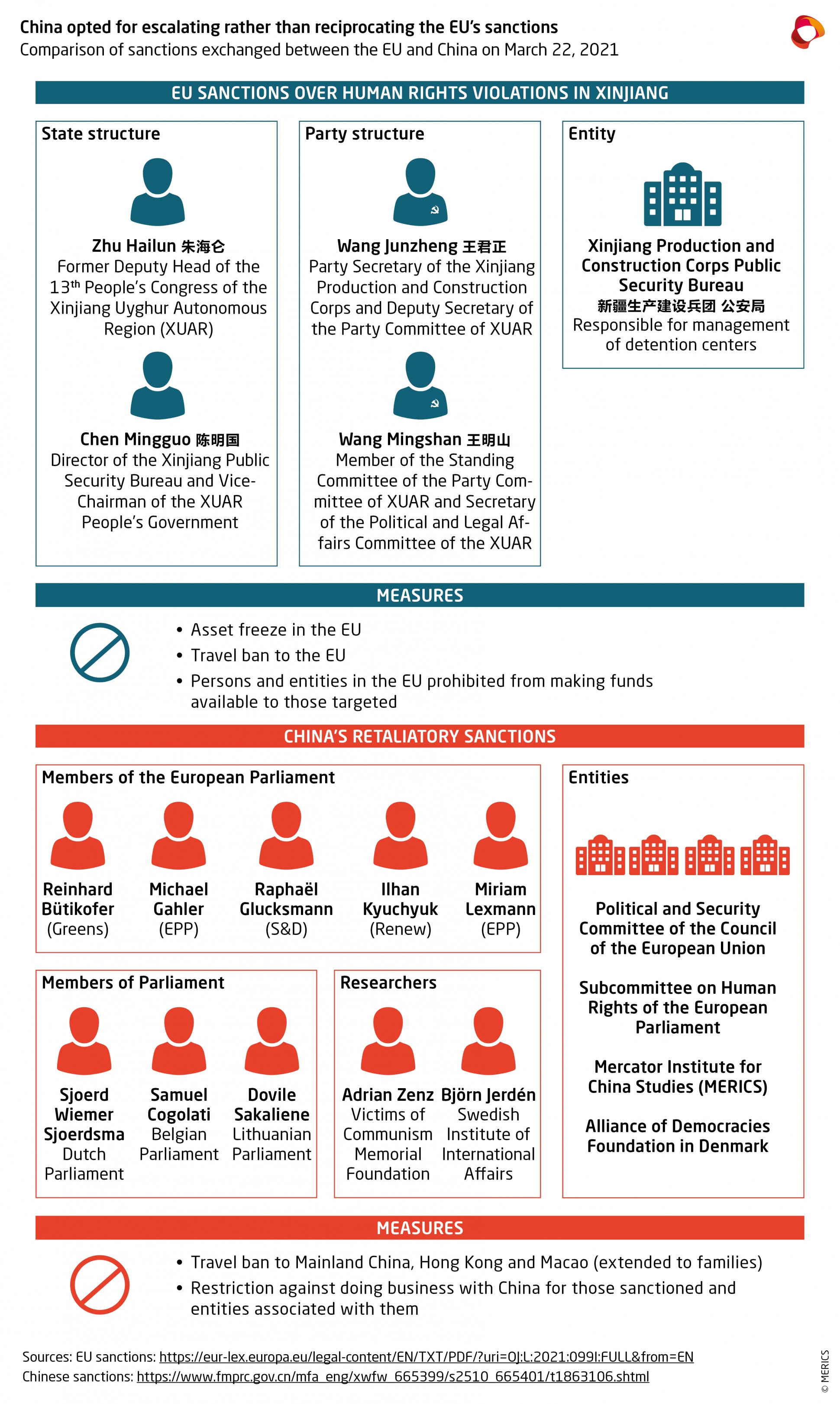

Although it was rushed through the legislative process without public consultation, following the exchange of sanctions between the EU, the UK, Canada, the US and China in late March, the work had started much earlier. Developing a legal framework to counter foreign sanctions and the extraterritorial effects of other countries’ legislation has been one of China’s legislative priorities over the last few months. The AFSL is another piece in China’s efforts to expand its retaliatory toolkit and its own extraterritorial reach.

The AFSL and other recent initiatives follow Xi Jinping’s call that “[i]n the struggle against foreign powers, we must use the law as a weapon and occupy the moral high ground of the rule of law, to say no to the saboteurs and spoilers”. With the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) getting ready to celebrate its 100th anniversary on July 1, it wants to be in a position to wield its new power and show itself capable of dealing with any external challenges to its rule.

Blocking, retaliating and proactive sanctions – a law to do it all

Chinese media and legal experts hailed the law as an important improvement to counter unjust foreign sanctions and a step up from the previous use of administrative measures to impose countersanctions, as was the case in March. But despite frequent comparisons to the EU Blocking Statute and the rhetorical focus on reciprocal, defensive action, the content of the law speaks a different language. Where the EU statute is limited to protecting natural and legal persons in the EU from having to comply with a clear list of restrictive measures imposed by other countries, the AFSL is a blocking statute, retaliatory regime and proactive sanctions legislation rolled into one.

The main purpose of the law is to preserve China’s “national sovereignty, security, and development interests”. Article 12 of the AFSL prohibits organizations and individuals – both Chinese and foreign – from helping enforce foreign discriminatory measures against PRC entities, and further gives those affected by sanctions the right to sue for compensation. This could have prevented HSBC from complying with US requests in the Huawei case, as one commentator noted. It could also affect companies that refuse to do business with the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps based on recent sanctions by the EU and other countries.

But the law also allows the Chinese government to implement its own countermeasures where it deems that “discriminatory restrictive measures” imposed by foreign states “violate international law and basic norms of international relations to contain or suppress our nation”. According to article 4, those who "directly or indirectly participate in the drafting, decision-making, or implementation” of sanctions or other restrictive measures can be placed on China’s countermeasures – i.e., sanctions – list.

The State Council can further include immediate relatives of sanctioned individuals, as well as individuals who have a management or controlling function in sanctioned organizations, or organizations in which sanctioned entities and persons play a key role. All of those placed on the list may be slapped with a freezing of assets, restrictions on doing business or otherwise associating with organizations and businesses in China, as well as unspecified “other measures”.

Although apparently focused on measures implemented by foreign states, a significant number of those sanctioned by China back in March were individual researchers or research and advocacy organizations. Indeed, article 15 of the new AFSL now explicitly allows for countermeasures against foreign organizations or individuals for “conduct that endangers our nation's sovereignty, security, or development interests”. In this sense, to describe it as a counter-sanctions law is misleading, as a wide range of actions by non-state actors can be deemed a sanctionable offense under the AFSL.

Interpreting China’s security and development interests

To grasp the potential scope of actions that can be sanctioned, it is important to understand how the Chinese party-state and thereby legal system interprets certain key terms. In 2014, Xi Jinping introduced the concept of “comprehensive national security”, which brings together different policy fields under an overarching framework, including sovereignty issues and development interests. It currently encompasses 16 types of security, ranging from traditional areas such as political security, territorial security, and military security, to new policy areas such as cultural security, scientific security and the security of China’s overseas interests.

From trade and investments to China’s global image and reputation – everything has become a matter of national security for the party. Creating a favorable international public opinion environment, i.e., strengthening China’s positions and keeping criticism on key issues in check, is seen as key for China’s development interests. This thinking underlies the expansion of Beijing’s red lines and core interests over the past years, hence the recent inclusion of “maritime issues” and “pandemics” to the list of sensitive topics. These now sit alongside longstanding sore points like Xinjiang, Tibet and Taiwan as issue areas where criticism or interference by foreign countries could warrant countersanctions by China.

China also reserves the right to employ countermeasures against foreign nations that violate the “basic norms of international relations in order to contain or suppress China”. But much like with the concept of national security, “basic norms of international relations” is a foreign policy concept formulated by the Chinese leadership. What this means exactly will be defined by Beijing, but it is generally targeted at countering “meddling in China’s internal affairs” – a charge that is regularly raised against parliamentary hearings and reporting on politically sensitive issues abroad.

New risk factors for foreign actors

Chinese officials and state media have pushed the narrative that the country will not attack unless provoked. But the scope of what is seen as a provocation has fundamentally changed in recent years. As such, the law is not just a hastily assembled instrument to retroactively legitimize China’s March sanctions or a momentary signal to the recent G7 summit. It lays the groundwork for further action in this space.

By including vaguely defined threats against China’s national security or activities that violate the basic norms of international relations as some of the types of behavior that could lead to countermeasures, Beijing has created a legal framework that enables it to target a wide range of actors and actions including documenting, criticizing or advocating against China’s policies and narratives.

Despite attempts by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to reassure foreign businesses that the law will have no impact on them, the AFSL should give foreign companies with a presence in China pause. Governments and non-governmental actors, too, should not underestimate the AFSL as a new risk factor. Fundamentally, the AFSL will support Beijing’s efforts to build a system for the extraterritorial application of its laws and to police behavior outside China’s borders.

Acknowledgements: The overview table on China's retaliatory toolkit (exhibit 1) was prepared by Rebecca Arcesati.