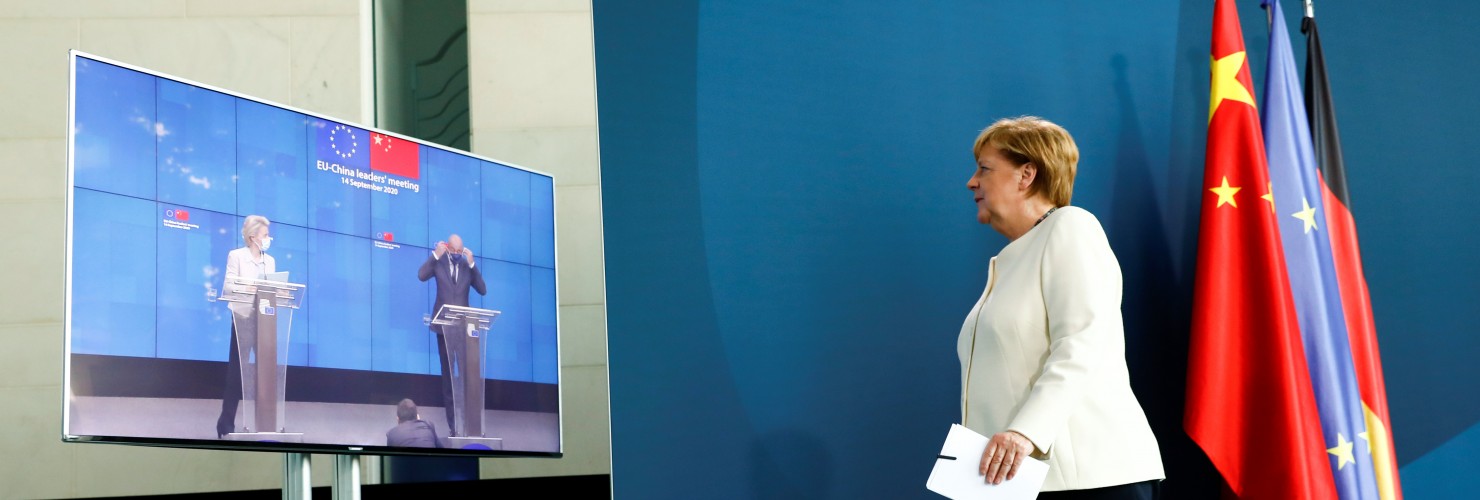

EU-China Opinion Pool: Germany's China policy after the election

The results of the recent elections in Germany have not provided a conclusive indication of how German China policy will develop post Merkel. However, with all the pieces in place, we can at least predict possible scenarios. Whatever happens, one thing is clear: the future of Germany-China relations will weigh heavily on the dynamics of EU-China relations in general.

In this round of our EU-China opinion pool, we ask several experts from fellow institutions and MERICS to answer the question:

Given the election results, what will Germany's China policy look like in 2022?

Constanze Stelzenmüller

Fritz Stern Chair at the Brookings Institution

The consensus appears to be that whatever the composition of the next German government, its China policy will be more hard-edged than Angela Merkel’s. The parties’ campaign platforms provide some evidence for this prediction.

But do the politicians and parties involved really have the ability to implement such a shift? This issue might become a test for the ability of Germany’s next government to produce political and policy coherence on a key issue of national security: to limit or mitigate the impact of German economic dependence on China, while at the same time drawing clearer red lines and using leverage to protect them.

Notably, the Foreign and Defense ministries — whose bureaucracies have come to a much clearer appreciation of the security risks associated with Beijing’s assertiveness — appear to be at best second-tier interests for the prospective junior coalition partners, the Liberals and the Greens. The ministries they really want are Finance and a Climate/Environment/Energy superministry. Both of these remits have obvious hard security aspects; but the framing for both emphasizes multilateralism, managing interdependence, and cooperative stewardship of public goods. And the man most likely to be chancellor at this point, Olaf Scholz, is the country’s acting finance minister.

This is where proposals to create a permanent national security council to advise the chancellery (mooted by this project of which I was a member) might help to create greater policy coherence. That, in turn, would help bring about greater EU cohesion on China. Which is needed both vis-à-vis Washington and Beijing.

Andrew Small

Senior Transatlantic Fellow at GMF

The most important changes to Germany’s China policy will not come quickly and will not even be characterized as “China policy”. The critical question is whether a new government can set in motion a transition in German and European economic strategy that is adapted to the systemic nature of the challenge that China now poses. This goes well beyond the usual market access and subsidy issues, and ranges from Beijing’s self-sufficiency drive and push to deepen and weaponize economic dependencies to the growing impact of Chinese non-market practices on European interests in third markets.

There is already a collective recognition from much of German industry and German officialdom that the progress made in sharpening the EU’s economic instruments in the last few years still falls short of the task. Mainstream opinion in the political parties has also shifted towards the view that - as the SPD’s China paper argued - the competitive dimension of the relationship with China is now foundational, defining even what forms of cooperation are possible.

Yet any momentum for a deeper rethink has been stymied by the Chancellery and a few major firms who wanted to eke out a little more from the old era of the Sino-German relationship. Whichever political constellation emerges, the very fact of a new government provides the opportunity for a pragmatic adaption to the new conditions that Germany and Europe face, without the same level of attachment to the legacy of the past. This is unlikely to be abrupt. No-one wants a hard decoupling, and the measures needed for an effective “diversification” agenda and the process of lining up Europe’s other major partners behind it will take time. But even starting a transition of this nature will have a conditioning effect on the entire approach to China, as the shadow of future hopes for the relationship gives way to greater realism about the China that is now emerging.

Ariane Reimers

Senior Fellow at MERICS

There will be some changes in the tonality of German China policy. But the probability that the future chancellor will continue a pragmatic China policy is nevertheless quite high. The possible future chancellor Olaf Scholz has a history of taking a business orientated approach towards China. His successor as First Mayor of Hamburg has just embraced the deal between the Chinese shipping giant COSCO and the Hamburg harbor company HHLA. And the chairman of the SPD parliamentary group is a known critic of taking a tougher stance on China.

On the other hand, the future coalition partners - both Greens and Liberals – are calling for a stronger value-orientated China policy and are ready to put the good bilateral relationship between China and Germany at risk. But it wouldn’t be very clever to have a chancellery trying to maintain good ties with China together with a frank and outspoken foreign office under a Green or Liberal minister.

Instead of sending mixed messages, the future German government should focus on a comprehensive European China strategy – and partner up with France, Italy et al. This would also have the aim of protecting all EU member states from Chinese harassment. In the end it is Europe and not Germany alone that has to find a path towards a China policy which reflects European interests and capabilities. That is the chance for the future coalition to find a common approach towards China – focus on Europe.

Mikko Huotari

Executive Director at MERICS

Germany’s next government must prepare for turbulent times in EU-China relations. Beyond setting substantive priorities, and to advance a pragmatic “principles-first” China policy centered on competition, the new government must also invest more in China competence, policy coordination and effective coalitions.

Competence: There is already strong China expertise in many federal ministries and in the German research community. But China today affects a whole new set of stakeholders and China competence remains high in demand. The next German government should continue to invest in independent China expertise and facilitate more “revolving doors” between policy-making, research and business circles.

Coordination: Internally, German China policy can still be better coordinated between ministries as well as with the Chancellor's Office. The key challenge here will be to link economic and security policy (“economic security”) more closely. The next government could also establish a foresight mechanism tasked to align the perspectives of key government stakeholders on China’s trajectory, anticipate risks and thus set guardrails for the work of the ministries.

Beyond Berlin, a more strategic China policy will require both wider and deeper coordination efforts. The subnational dimension of Germany’s China policy deserves more attention and alignment. On the European level, Germany should support an informal “Leading Small Group” of senior decision-makers in the Brussels institutions to hold things together. Other ministries, beyond the Foreign Office will need to step up their game on European China policy coordination, too.

Coalitions: The coming months offer a window of opportunity to further develop effective international coalitions on China policy. With Germany's G7 chairmanship, with the new European Indo-Pacific strategy and with a renewed focus on transatlantic coordination, the building blocks are in place. Concrete action from Berlin will be required to advance these efforts and promote connectivity on European terms, diversification in Asia and technology and trade standards with like-minded partners.

Noah Barkin

Managing Editor at Rhodium Group & Senior Visiting Fellow at GMF

Germany is most likely heading toward an “Ampel” coalition uniting SPD Chancellor Olaf Scholz with the Greens and Free Democrats. This is what a 6-month action plan for China policy could look like for such a new administration:

- Scholz overhauls the structures in the Chancellery, appointing an Indo-Pacific czar who chairs regular high-level inter-ministerial meetings on China and the wider region, feeding recommendations directly to the chancellor. In the first months of the government, the new czar puts together a consortium of leading economists and China experts to produce an in-depth study on the bilateral economic relationship, with scenarios, and policy recommendations. This feeds into a new national economic security strategy to be produced within the first six months of the new government.

- The new German government begins talks with France on holding a full-day summit of EU-27 leaders on China and broader Indo-Pacific policy around the June European Council. The aim is to build on the March 2019 Strategic Outlook, producing a new list of action points and common principles for EU interaction with Beijing. This is the first of what become annual meetings of EU-27 leaders on Indo-Pacific strategy. Host Olaf Scholz shares details of the EU’s new approach with international partners at a G7 summit.

- The new German government announces a doubling of federal funds dedicated to boosting knowledge of China in German educational and research institutions, as part of a broader initiative to foster closer ties between the German and Chinese people. At the same time, the Federal Education Ministry begins negotiations with states on a strict new set of ground rules for the continued operation of Germany-based Confucius Institutes.

- After travelling to Paris, Brussels, Washington, Jerusalem, Tokyo and Delhi, Chancellor Scholz makes his first trip to Beijing, without a large industry delegation in tow. He expresses desire to work closely with the Chinese government to deliver bolder action on climate, but voices concern about the human rights situation and growing state pressure on European companies in China. Behind closed doors, Scholz delivers a message to Xi Jinping that any steps to force reunification with Taiwan will change the German and European relationship with China in fundamental ways, triggering far-reaching economic sanctions.

Volker Stanzel

Senior Distinguished Fellow, German Institute for International and Security Affairs

A new China policy begins in Paris. In recent years, Germany's China policy has suffered most from the lack of a common European approach. European coherence is only achievable if Germany and France first work together to define content and drive EU unity. Forging a coherent and dynamic European China policy is therefore the first task.

The second is to try to get the UK on board. Next comes the G7. With a US president who is not yet entirely reliable, it is imperative to embed a future transatlantic China policy in a larger solid framework. That means Japan and Canada must have a say. Finally, the new German and European China policy must be regularly and systematically consulted and coordinated with the relevant powers of the Indo-Pacific: the Asian Quad members and ASEAN, preferably coordinated with the US.

Right, the content! There are two essential components:

- Expansion of German and European relations with China wherever beneficial to both: trade, investment, connectivity and climate policy;

- Taking a position against any violation of the rules of the international system including its security aspects, against unequal treatment of Europeans in China as compared to Chinese in Europe, and against human rights violations. These substantive elements of a future China policy are obvious. What counts is the international embedding and anchoring. None of the parties currently considered to be the sponsors of the new federal government are likely to disagree here. The litmus test will be in the implementation.