China’s arms industry is increasingly global, but don’t expect it to supplant NATO’s counterparts any time soon

No. 2, August 2024

China’s military modernization has been a central plank of President Xi Jinping’s policy agenda. Historically, China’s arms makers have focused almost exclusively on supplying the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). However, over the last decade, they have begun to look for overseas markets to supplement sales and support Beijing’s geopolitical goals. Arms sales are an often-overlooked aspect of China’s global security and economic footprint and can present challenges to European arms makers in overlapping markets. European policymakers and corporates need more knowledge and awareness of this issue. This edition of the China Global Competition Tracker looks at China’s arms industry and its footprint overseas. First, MERICS Lead Analyst Helena Legarda examines Beijing’s strategy of arms sales overseas and how it might develop in the future. Next, Lead Analyst Jacob Gunter looks into Norinco, one of China’s key land equipment makers, as a representative example of the overseas push by China arms industry.

China aims to expand its overseas arms sales, but is beset with headwinds

China has established itself as a major arms exporter, building on years of military modernization policies that have strengthened its defense industry. Beijing has set its sights on exporting arms as China is now able to produce most of its military equipment domestically, reducing its dependence on imports from Russia and elsewhere. Sales teams from China’s ten major defense SOEs operate across the globe in search of new customers and in support of Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions.

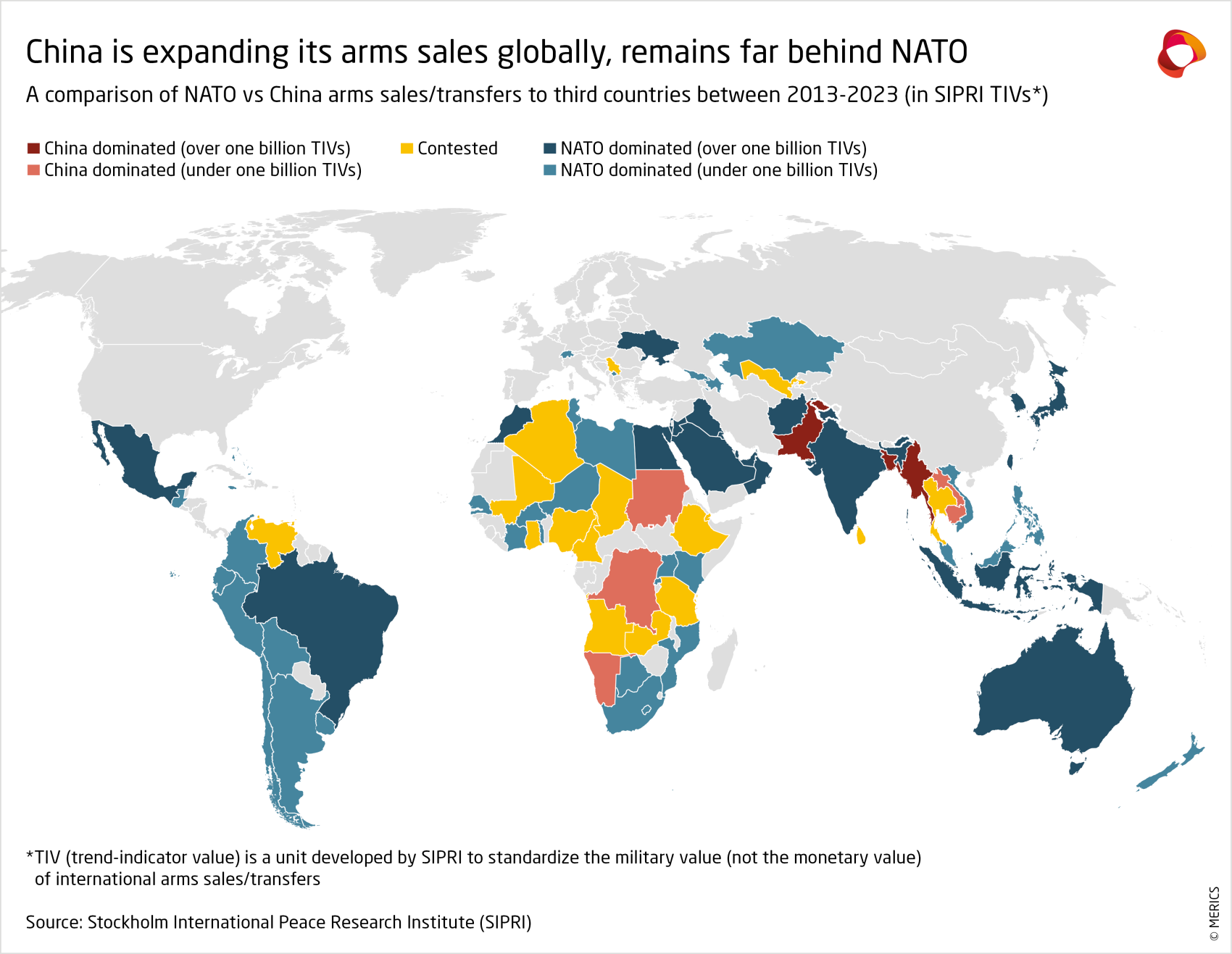

The strategy is paying off. China had 5.8 percent of all global arms exports between 2019 and 2023, making it the fourth largest supplier of conventional weapons, after the United States, France and Russia. Roughly 40 countries purchased Chinese military equipment in the 2019-2023 period, despite the Covid-induced drop in China’s share of global arms exports in those years. Today, Chinese weapons are gradually becoming dominant in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, and are making inroads in Central Asia and the Middle East. There are economic and geopolitical implications for European governments and arms industries, though the intensity of the competition should not be overstated. Chinese arms exporters still face serious limitations that could constrain further sales growth.

An indiscriminate, cost-effective provider

China’s success in expanding its overseas arms sales rests on the attractiveness of its offer to developing nations. First, Beijing exports nearly every category of conventional military equipment, from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and missile systems to submarines, naval vessels and fighter aircraft. Chinese weapons providers also benefit from Beijing’s absence from key international arms control pacts intended to regulate trade in conventional weapons (the Wassenaar Arrangement) and missile technology and delivery systems (the Missile Technology Control Regime). Despite the growing export restrictions on armed UAVs imposed by Beijing, this means that Chinese firms are able to sell certain platforms, such as some types of armed drones, that European or US firms are banned from exporting. Nonetheless, Beijing does not allow export of China’s most advanced variants, to preserve its military advantage. So far, platforms such as China’s 5th generation J-20 fighter remain exclusively for PLA use.

Chinese platforms sell for less than Western equivalents and their makers often offer flexible payment conditions. Buyers may also perceive Chinese weapons exports as having fewer strings attached than Western ones.

Chinese firms sell indiscriminately. They have demonstrated their willingness to sell equipment to all kinds of governments and regimes, without regard for their human rights record, degree of stability, or likely intentions for using the weapons. China has continued selling weapons to Myanmar throughout the ongoing civil war, for example, and there is some evidence of Chinese-made drones originally sold to nearby countries being used during the war in Yemen. Chinese providers reportedly do not demand end-user certificates, which are meant to prevent weapons sales from being diverted to other actors and to ensure authorized users use them only for authorized purposes.

Chinese arms makers’ indiscriminate sales approach is one reason why most Chinese arms manufacturers appear on the United States’s sanctions lists. Some Chinese firms’ (such as Norinco’s) military support for Iran triggered some of the earliest such sanctions in 2003. The list expanded rapidly under the Trump and Biden administrations. Chinese arms makers tend to be listed for their part in modernizing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and assistance towards Russia’s war in Ukraine. The EU has no equivalent sanctions on China’s arms industry, although it has maintained an arms embargo on China since 1989.

Pushing to grow

China is pushing to expand its global market share, zeroing in on geopolitically important regions such as South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa. Sales bring clear economic benefits to its defense sector state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the sluggish national economy. Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) shows arms revenue made up 27 percent of Norinco’s total revenue in 2022, and 25 percent at the Aviation Industry Corporation of China’s (AVIC). Although these are far lower shares than Lockheed Martin’s 90 percent or Raytheon’s 59 percent, they are nonetheless significant numbers for some of China’s largest SOEs.

China’s arms exports are also a tool in Beijing’s geopolitical arsenal, as arms exports can lay the foundation for closer ties on other issues. Beijing is able to use arms sales to build influence and closer partnerships with nations in the Global South, which serves its strategic goal of forging a coalition of countries to push back against Western dominance.

China’s share of arms imports in the Americas and the Middle East remains small: US and European suppliers continue to be dominant in those regions, but Beijing is rapidly making inroads in Africa and in Asia. China’s share of total arms exports to all of Africa has remained largely stable since 2009 (at around 12 percent), unable to compete with the United States and Europe. But the dynamics are shifting in Sub-Saharan Africa, where China has become the top supplier, overtaking Russia. China’s share of arms exports to South and Southeast Asia is also growing rapidly, partly thanks to sharp drops in Russian exports since the start of full-scale war against Ukraine.

China’s arms offer has limitations

China’s arms exports are not growing evenly. They are, in fact, extremely concentrated in a handful of regions and countries. Between 2019 and 2023, 85 percent of all Chinese arms exports went to Asian countries, and 61 percent went to a single state: Pakistan. Islamabad purchases the bulk of its military equipment from China, despite being a NATO global partner. Pakistan has even signed agreements to co-produce the JF-17 fighter jet, the K-8 light attack aircraft and other Chinese systems. China remains a relatively niche arms provider, selling mainly less advanced weapons at a low price point to a small number of countries. Outside of a handful of nations, such as Pakistan or Bangladesh, most buyers of Chinese weapons are one-off or ad hoc customers, which limits the customer base of Chinese weapons makers and can give an inflated impression of the global reach and spread of Chinese arms exports.

Chinese firms’ only-partial success at expanding their global customer base is because of the limitations of their offer. Chinese weapons are largely untested in combat and also suffer from quality and performance problems. Importing countries may lack personnel with the expertise to resolve technical issues that emerge, or face problems obtaining replacement parts. Chinese suppliers have often shown little accountability in such cases. Nigeria, for example, had to return seven of the nine F-7 fighters it had purchased to China in 2020 for maintenance as it was unable to get them serviced locally by the supplier. Myanmar reportedly ended up having to ground the majority of Chinese jets used by its military in 2022 because of structural cracks and issues with their radar systems.

Western countries, in particular the United States, have also warned repeatedly that Chinese systems cannot and will not be integrated with Western-produced ones, largely for interoperability and security reasons. Countries that operate more advanced Western weapons systems or wish to buy them face a clear choice between Chinese weapons or US and European ones. The threat of Western sanctions has also constrained China’s ability to sell weapons to Russia since the start of the war in Ukraine in 2022, forcing China to limit itself to transferring dual-use technologies and components. This shows that Europe and the United States, if they can achieve consensus, have some leverage to shape third countries’ arms buying decisions, but also the willingness of Chinese firms to sell to sanctioned countries.

True competitors?

Below the surface, the numbers show most countries purchase the majority of their weapons either from China or from NATO allies, including Europe and the United States. However, there are a handful of notable exceptions. Pakistan and Thailand continue to buy from both China and Western suppliers, likely leveraging their status as NATO partners and US allies. Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, is the only country to appear in the top 10 recipients list for both China and NATO allies in the 10 years between 2013 and 2023. Nonetheless the difference in volume is staggering: 28,448 million in SIPRI’s trend-indicator values (TIV) from NATO allies compared to only 366 million from China.

Chinese firms are trying to break through this either/or pattern by adapting some of their products. Some Chinese equipment such as tanks or aircraft reportedly use standard NATO fitments for accessories and parts, to make the acquisition of parts easier in the global market. At the 2024 Eurosatory defense exhibition in France, Norinco presented howitzers and other artillery systems that meet NATO standards in a bid to boost exports.

Competition between Chinese and Western providers will only intensify in years to come as China tries to boost its exports and expand its global influence. But there are clear limits to what Beijing can offer – its refusal to offer direct alternatives to Western platforms by exporting its more technologically advanced equipment, the limited interoperability with Western systems, and worsening geopolitical competition are likely to hinder China’s efforts.

China, however, is also pushing to achieve dominance in advanced technologies with dual-use applications, from autonomous systems to quantum computing, and is leveraging its strategy of civil-military fusion and its access to European and US technologies and know-how to get there. These dual-use technologies and components are increasingly being exported globally. They make up the bulk of China’s military support for Russia since the start of the war in Ukraine. As Chinese firms encounter more obstacles to their sales of conventional weapons systems, it is possible they will shift their focus towards the export of dual-use goods and technologies for military applications – creating a whole new set of challenges for European governments and military industries, and a new arena of competition.

Company profile: Norinco

A closer look at an individual Chinese arms manufacturer’s approach to domestic and international sales gives a better sense of how the sector acts on the global stage. Unfortunately, and also typically, there is very little open-source information about Norinco Group (the Northern Industries Group), which is China’s largest arms maker. Norinco Group scores 9/100 on the Transparency International Defense & Security Transparency Score. As a state-owned enterprise (SOE) overseen by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), and ultimately the State Council, Norinco is not bound by many public reporting requirements. Nor does it have an overseas listing which would open it to scrutiny. These factors limit research into the company’s internal workings and its strategies at home and overseas, but there are significant indicators to extrapolate from.

Norinco is China’s largest arms manufacturer, but is only one part of its weapons industry

China’s defense industry is spread across several key state-owned enterprises, though President Xi Jinping’s push for “civil-military fusion” is changing the boundaries between the civilian and defense sectors. The largest players in the sector are:

- Norinco Group (the Northern Industries Group), which leads the production of land equipment and munitions and its cousin the Southern Industries Group

- The China Electronics Technology Group which makes radar systems, communications equipment, and other electronic platformsT

- he China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC), which builds most of the ships for the PLAN

- The Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) which makes most of China’s military aircraft and the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) which mainly covers China’s space program but also has weapons-making unit.

Norinco is a major supplier to the PLA and provides a range of equipment and ordnance to primarily to the PLA’s ground forces, (though it is allegedly the sole arms manufacturer in China which sells to every branch of the military) including:

- Main battle tanks and light tanks

- Armored vehicles

- Motorized/self-propelled and traditional artillery

- Multiple Launch Rocket Systems

- Motorized/self-propelled integrated air defense systems

- Ground and anti-air missiles (these tend to be comparable to handheld systems like Javelins/Stingers, rather than longer range)

- Cruise missiles

- Radar systems

- Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs/drones)

- Infantry equipment and small arms

In overseas markets, Norinco has defense contracts with some countries as the direct supplier of military equipment, though it does not sell its full range anywhere outside China.

Its direct sales focus on types of equipment most in demand from developing countries, where there is less demand for Norinco’s most advanced and powerful products. In these markets, it typically sells the more basic infantry equipment and artillery, lighter armored vehicles and motorized equipment. It also is a sizeable supplier of police, counter-terrorism, and riot control equipment to police forces and paramilitaries. Many developing countries regard Norinco’s product lines favorably based on their specific needs and the low costs. China also overlooks human rights concerns so its deals are less likely to come with strings attached. Norinco also engages in licensing its equipment to international partners rather than exclusively through exports of material made in China.

Less than one third of Norinco’s revenue is from weapons, a typical pattern for its Chinese peers

Although Norinco is China’s largest arms maker, only around 27 percent of its revenue comes from arms sales. At home and abroad, Norinco is involved in other sectors that are either mixed/potentially dual use or civilian business lines. Some are linked to key resources essential for national security like energy and minerals/materials, while other business lines serve to generate revenue and profit to compensate for the low margins and weak profits Norinco receives as a PLA supplier.

Many of its overseas business lines are managed through Norinco International Cooperation Ltd. Its overseas interests extend to

- Petroleum exploitation and trade, including in the Middle East, West Africa, and Latin America

- Mineral exploitation, processing, smelting, and trade in Africa and Latin America

- Engineering, especially for transportation (mostly rail), energy grid equipment and municipal construction, in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia-pacific

- Civil blasting operations in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Oceania

- Civilian vehicles and heavy equipment in Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and the Middle East

Like Norinco, other major Chinese arms manufacturers get only a minor share of their revenue from arms sales. Among China’s top five arms makers, the highest share of revenue derived from arms sales is around 44 percent at China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. At the others, it ranges between 25 percent to 32 percent. By contrast, among the top five US players, the lowest share of revenue derived from arms sales is around 44 percent at Boeing, with the highest share being 90 percent at Lockheed-Martin. European arms makers, likewise, are predominantly dedicated to arms production and adjacent civilian applications.

The most probable explanation for these varied business lines is that many of them predate reforms to China’s military and defense systems undertaken by President Xi. At the start of the reform and opening up period in the late 1970s and 1980s, Deng Xiaoping encouraged the PLA and defense-oriented SOEs to get into civilian, commercial businesses. The purpose was twofold – to encourage development wherever possible and to supplement the PLA budget at a time when state resources were focused on economic growth. President Jiang Zemin later pushed back on this in 1999 when he called for PLA divestment (which had a limited effect) and reformed the defense industry by splitting up the major players and making them bid for PLA contracts. The separation of Norinco (Northern Industries Group) and Southern Industries Group dates from this period; the northern company was more successful at winning bids and hence became far larger than the southern one.

Military modernization has been a pillar of President Xi’s agenda. In November 2015, he launched a three-year effort to clean up the PLA and force it to divest from the many companies the military used to own and operate. This time, the divestment drive was more thorough and effective. Why, therefore, do Norinco and other Chinese defense industry players still have so many civilian, commercial lines of business after the PLA itself has had to divest? Perhaps because while the PLA itself being a commercial player contributed to corruption and distracted the military from its core functions, there are benefits to Norinco and its peers maintaining commercial business lines. They support the military modernization strategy by bringing in more revenue from varied sources, meaning more capital to invest in R&D for defense technologies.

Norinco’s future is complicated by structural issues at home and geopolitical developments abroad

Norinco’s future is rife with challenges and opportunities based in the protected status of China’s arms industry and Beijing’s ability to and appetite for competing with US and European arms makers in third markets.

Domestically, China’s arms makers have little competition – the country’s arms industry consists of a small group of SOEs crowding out others. Beijing’s failure to create a robust procurement system and the conditions for real competition to emerge in the sector is both good and bad for Norinco’s future. The firm will benefit from its protected status and guaranteed PLA demand, albeit at low margins. The resulting economies of scale help in seeking more profitable markets abroad. However, lack of competition could stymie innovation and global competitiveness for Norinco and China’s arms sector more generally, given their platforms do not currently offer technological parity with western ones. Norinco and others could become cemented into their current global position – one where they focus on markets under western sanctions, where there is little competition, or markets where cost effectiveness is the primary concern.

Compare that with the United States, which has a huge number of arms suppliers. There are some giants, but many of the land systems are drawn from a pool of many players in fierce competition with each other. The situation is similar in the EU and the United Kingdom, where higher numbers of firms exist, even if many of them are smaller players. Norinco’s only real competition for land systems is Southern Industries Group. Both are SOEs that enjoy an implicit guarantee so they need not worry about meaningful competition in China and can take much of their arms business for granted.

One issue worth tracking is the trend of civil-military fusion in China. It is a core concept in President Xi’s agenda, the idea being to incorporate more civilian technology leaders into China’s arms industry to improve platform capabilities and possibly create unique advantages for the PLA. In future, this trend may help to compensate for the arms makers’ difficulties in producing technologically-competitive platforms.

Finally, Norinco’s global arms sales will be heavily shaped by geopolitical factors beyond its own control. This fact is not unique to Norinco, nor to China’s arms sector – most countries have strict rules governing where and to whom their arms companies can sell which kinds of platforms. Beijing’s negotiations with partner countries will be a key factor in Norinco’s ability to expand its global footprint. Without Beijing’s permission and diplomatic support, Norinco and others would be unable to expand global sales significantly. However, Norinco is making the most of new opportunities globally because its competition from Russian firms has diminished due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. On the flip side, Norinco’s ability to expand into many countries is likely to be limited by old and more recent sanctions and other possible measures by the United States, EU, and their partner countries, plus a range of arms control treaties and agreements and more generalized Western pressure on the governments of third market countries.

Global China Inc. Updates

Belt and Road Initiative politics

Chinese firm starts construction of Serbia’s national football stadium

In May, PowerChina began construction of the National Football Stadium in Belgrade. The Serbian government has reportedly invested EUR 350 million in the 52 000-seat sports stadium and associated events center, and taken on EUR 190 million in loans to build infrastructure to support the venue.

China and Pakistan agree on CPEC Expansion

In June, during a visit to China by Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, both nations agreed to further upgrade the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The talks led to the signing of several key agreements to expand infrastructure, industrial cooperation, and technological exchange. These include the rehabilitation of the Karakoram Highway and improvements to Gwadar Port, as well as the establishment of new growth, livelihood, and innovation corridors.

China - Kyrgyzstan - Uzbekistan railway goes ahead

The governments of China, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have signed a BRI-related agreement to build a new 523-kilometer railway connecting the three countries, at an estimated cost of USD 8 billion. The agreement signed in Beijing on June 6 covered cooperation on the financing, construction, operation and maintenance of the new railway. Construction is due to start in October.

Digital, health, and technology

JV battery plant in Finland gets environmental permit

A Chinese-Finnish joint venture, 60 percent-owned by Chinese company CNGR Advanced Material, was granted an environmental and a start-up permit for its battery material plant in February. The EUR 500 million plant is to produce precursor cathode active material (pCAM) used in manufacture of lithium-ion batteries. The project in Hamina, 150 kilometers from Helsinki, drew strong public concern over wastewater and air emissions.

Huawei overtakes Samsung as top foldable-phone maker

Huawei Technologies overtook Samsung Electronics as the world's leading manufacturer of foldable smartphones in the first quarter of 2024, seizing the top spot for the first time with the popularity its new 5G models. China-based Huawei accounted for 35 percent of foldables shipments in the first quarter, up 21 percentage points on Q1 2023, according to Hong Kong-based Counterpoint research.

Energy, resources, and commodities

Huadian group plans USD 2.4 billion green hydrogen project in Vietnam

In March, China’s state-owned power giant Huadian Group unveiled plans to build Vietnam’s largest green hydrogen project, in a joint venture with Vietnamese electricity producer Minh Quang. The USD 2.4 billion plant is projected to produce 60,000 tonnes of green hydrogen a year, using around 1 gigawatt (GW) of alkaline and PEM electrolyzers in the process. It is to be powered by 1.2GW of wind power and 800 megawatts (MW) of solar.

China’s State Grid signs large power transmission contract in Brazil

In April, China’s State Grid signed a contract to build Brazil’s northeast ultra-high voltage (UHV) transmission lines, after winning the bid for the USD 3.6 billion project last year. An estimated 1500 km of new UHV lines will deliver 5 million kilowatts (KW) of power from northeast Brazil, mainly from wind and solar farms, to urban areas in the south. The transmission lines are expected to be operational by 2029.

Egypt agrees a joint USD 2 billion Chinese-Korean green hydrogen project

In March, China’s state-owned CSCEC (China State Construction Engineering Corporation) and Korean firm SK Ecoplant signed an agreement with Egyptian authorities to jointly construct a green hydrogen and ammonia production plant in the Suez Canal Economic Zone. The USD 2 billion project, scheduled for 2029, aims to generate 778MW of electricity, producing 50,000 tonnes of green hydrogen and 250, 000 tonnes of ammonia per year.

Chinese lithium firm acquires 100 percent of Mali Lithium

In May, Chinese firm Ganfeng Lithium became sole owner of Mali Lithium with its USD 342 million acquisition of Australia’s Leo Lithium’s 40 percent stake. The Australian firm cited risks associated with Mali’s new mining code as the reason for selling its shares. Mali Lithium holds the license for the Goulamina mine in southern Mali.

Trade and finance

Chinese venture capital and private equity target Middle Eastern investors

Chinese venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) companies are increasingly targeting Middle Eastern investors, with over 200 Chinese VC and PE firms visiting the region last year. They have suffered a sharp downturn in fundraising and investment from their traditional backers in Europe, the United States, Japan and South Korea due to geopolitical tensions — the amount of money raised by Chinese VC and PE firms slumped 18.9 per cent in 2023.

Argentina renews USD 5 billion currency swap with China

In June, Argentina’s Central Bank renewed a USD 5 billion tranche of the currency swap it has with its Chinese counterpart, USD 3 billion of which matured in June and the rest in July. The decision means Argentina must start paying the maturities in 2025 and 2026, rather than this year.

Retail

Chinese retailer Miniso shifts focus overseas

Chinese low-cost retailer Miniso plans to rapidly expand overseas by opening roughly 600 overseas stores this year to shift away from weak domestic markets. It plans to open only around 400 stores in China this year.

Transport and logistics

Cambodia breaks ground on China-funded USD 1.7 billion canal

In August, Cambodia broke ground on a controversial, China-funded canal from the capital, Phnom Penh, to the sea, despite environmental concerns and the risk of strained relations with neighboring Vietnam. The USD 1.7 billion, 180-kilometer canal will connect the capital with coastal Kep province, giving access to the Gulf of Thailand. Cambodia hopes the 100-meter wide, 5.4-meter deep canal will lower the cost of shipping goods to its sole deep-sea port, Sihanoukville, and reduce reliance on Vietnamese ports.

CSSC to build USD 6 billion worth of LNG vessels for Qatar

In April, state-owned oil and gas company Qatar Energy signed a USD 6 billion contract with China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) for 18 liquefied natural gas (LNG) vessels. The ships will be the largest of their kind in the world, at 344 meters long, with a capacity of 271 000 cubic meters. They will be built at China’s Hudong-Zhonghua Shipyard for delivery between 2028 and 2031.

CRSC to supply signaling systems for iron mine railway in Guinea

In April, Chinese railway signal manufacturer CRSC won a contract to supply systems to a major railway project in Guinea. The 552-kilometer railway connects Maribaya port with the Simandou iron mine, the world’s largest known iron ore reserve. The deal, worth RMB 1.2 billion, is CRSC’s largest overseas contract to date.

Laos Thailand cross-border railway passenger train starts operations

The Chinese-built cross-border railway passenger service between Laos and Thailand officially went into operation on July 19. The first train traveled between the two countries’ capital cities in approximately 12 hours. The new rail service will enhance regional connectivity and economic integration.

- Endnotes

1 SIPRI’s trend-indicator value (TIV) is a system designed to measure the volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons using a common unit that allows for the measurement of trends in the flow of arms to particular countries and regions over time. The TIV is based on the known unit production costs of a core set of weapons and is intended to represent the transfer of military resources rather than the financial value of the transfer. For more information, see https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers/sources-and-methods