Impatient for tech breakthroughs, the Communist Party is pushing aside private initiatives

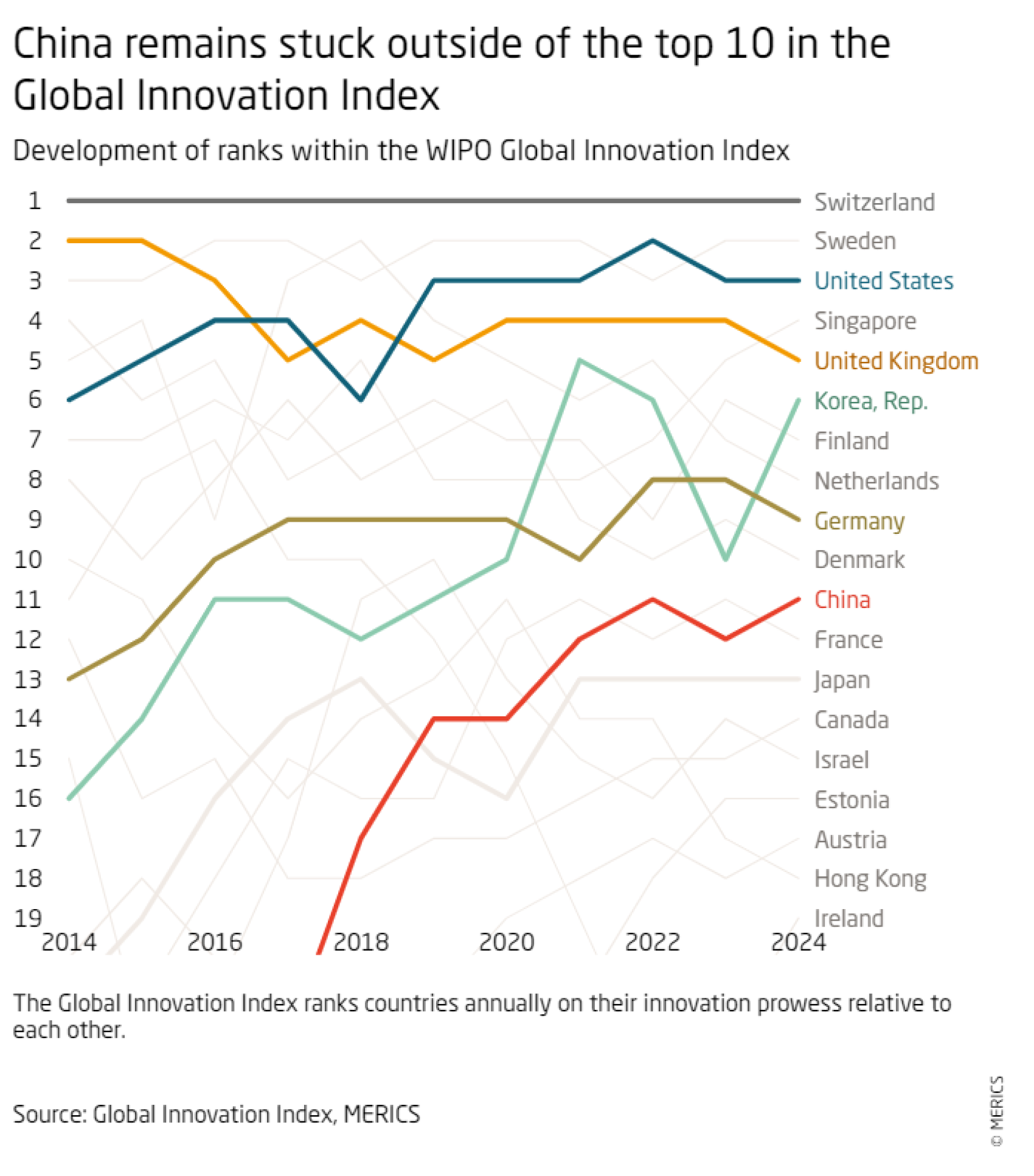

In 2024, China’s leadership continued to emphasize the centrality of science and technology to the country’s future. Results have been mixed, which is best reflected by China’s slow progress on the Global Innovation Index, an authoritative annual ranking published by the UN-affiliated World Intellectual Property Organization (see graph below).

With the current challenging international environment, China needs to become more self-reliant in strategic technologies. The US announced a new round of export controls on December 2 targeting AI memory and chip tools. More turbulence is expected in 2025 as Donald Trump takes the helm in the US.

In China, the Communist Party is showing its impatience with the slow pace and has been taking control of the situation – at the expense of state organizations and private capital. Party organizations in half of China’s provinces have set up branches of the Central Science and Technology Commission. Without party guidance, local government is too fragmented to push science and technology forward effectively, says professor Liu Fan of the Wuhan University School of Marxism.

The tech hub Hefei may be an exception – the Hefei model requires local government officials to act like venture capitalists. President Xi endorsed the model in his October visit to Hefei. However, this approach is popular because China’s actual venture capital investments have declined 40 percent year on year, resulting in fewer Chinese unicorns – privately held startups valued at over USD 1 billion.

The incoming European Commission has also declared research and innovation to be at the heart of the economy. But there is considerable division over how to achieve this. Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank, proposed industry-specific measures, drawing criticism from economists who would rather improve the business environment for all start-ups in Europe.

Science and technology have moved to the center of global politics, and global technology supply chains are more likely to be based on politics than economic rationale. Being cut off from Western-led technological developments will make it costlier for China to remain competitive across all strategic technologies.

Jeroen Groenewegen-Lau, Head of Program for the Science, Technology and Innovation team at MERICS, says: “The Communist Party of China increasingly stakes its legitimacy on its ability to deliver scientific and technological progress. In its eagerness to speed up tech development, it undermines the role of the private sector and the state in China’s innovation ecosystem.”