EU: De-risking from China hits the road

You are reading the EU chapter from the ETNC Report 2024 "National Perspectives on Europe’s de-risking from China". Go back to the main page.

Supply tensions and broadening geopolitical divergences with Beijing have pushed the European Commission to make long-in-the-making de-risking the guiding mantra of bilateral relations as part of a broader European Union economic security agenda. The introduction of measures to bolster the EU’s geoeconomic standing has accelerated. Policies have been rolled out to support EU-based semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and green-tech industries. A dedicated act and targeted partnerships have been produced to secure the supply of critical raw materials. The consequences of this new approach are yet to fully materialize. The natural lag between policy decisions and impacts is amplified by the EU’s complex internal machinery. At the same time, more serious securitization of economic interactions with China would require greater financial resources and more political capital from member states.

According to President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, “We see a strong push to make China less dependent on the world, and the world more dependent on China”. Nine months later, having made de-risking the mantra of the EU approach to bilateral relations, followed four months after that by an economic security agenda, she was clear: “The EU’s de-risking strategy had been slowly brewing for some years, arriving after years of intense introspection regarding the European economic approach to China and the world”.

A recalibration of European views as part of a broader questioning of globalization, openness and interdependencies

Long gone are the days of a univocally positive perspective on economic openness. The results of the British referendum on leaving the EU and the election in 2016 of US President Donald J. Trump signified the end of an era. Trump’s rejection of globalization set a new tone. At the same time, China under Xi Jinping was also changing course, moving away from the reform and opening up initiated in the 1980s towards a more centralized economy that prioritizes technological upgrades and regime security. During the Covid-19 pandemic, it became ever clearer that the US and China were headed towards more confrontation and away from a rules-based and generally cooperative globalization.

These developments affected the EU and led to tensions in relations with China. An early indicator was the March 2019 Communication by the Commission on China, which moved away from a focus on cooperative and mutually beneficial relations and described Beijing as a partner, competitor and systemic rival. Around the same time, discussions on “open strategic autonomy”, that is, Europe assuming an active role on its own instead of amplifying or following US policies, gained momentum.

The EU started de-risking before talking about it

Fiercer competition and rougher behaviour taking root in the globalized world pushed Europeans to initiate economic risk-reduction measures even before the concept became popular. An EU framework on the screening of foreign direct investment (FDI) was established in 2019, largely in response to inflows of Chinese investment.

This framework requires EU member states to establish such screening under certain guidelines, alongside soft intra-EU coordination. The creation of a Chief Trade Enforcement Officer was also agreed to better shield the single market from foreign distortion.

A few months later, the EU began to develop an anti-coercion instrument, initially in response to US pressure to stop the Nord Stream II pipeline from importing more Russian gas into Europe. The EU Toolbox on 5G cybersecurity of January 2020 largely sought to exclude Chinese suppliers from European telecommunications networks.

During the pandemic, Europeans realized that many critical supplies of medical products depended on deliveries from China, triggering a broader debate on securing critical inputs and infrastructures. The first-ever Commission report on trade dependencies featured China prominently as the origin of half of all European dependencies. A second zoomed in on six critical sectors, once again identifying dependencies on China in half of these.

To reduce dependencies, the EU framework on prohibiting state aid was relaxed in November 2021 for “Important Projects of Common European Interest” (IPCEI). Alongside IPCEIs on microelectronics and batteries, regulations were put in place to provide more comprehensive support to specific critical sectors. Efforts were initiated to improve the resilience of “critical entities” to cyberattacks, among other risks not specific to China but certainly with China in mind.

The de-risking concept is a push for a common European approach to China

With international tensions on the rise, Europe ramped up its economic security efforts and de-risking from China. Beijing’s pro-Russian neutrality following the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine led to a deterioration in bilateral relations. Common ground had already been eroded as China in December 2021 took coercive measures against Lithuania for allowing the Taiwan representative office in Vilnius to refer to Taiwan, rather than Chinese Taipei.

Washington also played a role, albeit secondary. The new administration under Joe Biden did not significantly reverse Trump’s “America first” approach. The Chips and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, involving billions of US dollars in subventions for local production, dashed any hopes the US would re-embark on a truly collaborative agenda. In addition, US pressure to align with its China strategy steered Europeans towards developing a more consistent approach of their own.

These developments culminated in President von der Leyen explicitly making de-risking and economic security the main strategic goals on China in March 2023. She defined the objective as “minimising risks arising from certain economic flows (…), while preserving maximum levels of economic openness and dynamism”. In setting out the de-risking concept, von der Leyen sought to push for a clearer joint European approach to China. The emphasis on reducing risks came alongside one on cooperation with China, thereby discounting unrealistic calls for a decoupling. A “Joint Communication on Economic Security” published in June 2023 offered a structured and consistent framework for safeguarding the EU’s international position.

The Commission now has a comprehensive and formal de-risking strategy

By introducing this multidimensional and ambitious plan a year before the elections to the European Parliament, the Commission hopes to steer discussions during the final months of its mandate – and probably beyond. It has set out a structured framework for approaching and addressing de-risking. Four types of risks are identified: resilience of supply chains, critical infrastructure, technology leakage and weaponization of dependencies. In cooperation with the member states, the Commission will undertake internal risk assessments for each, which will be updated on an annual basis.

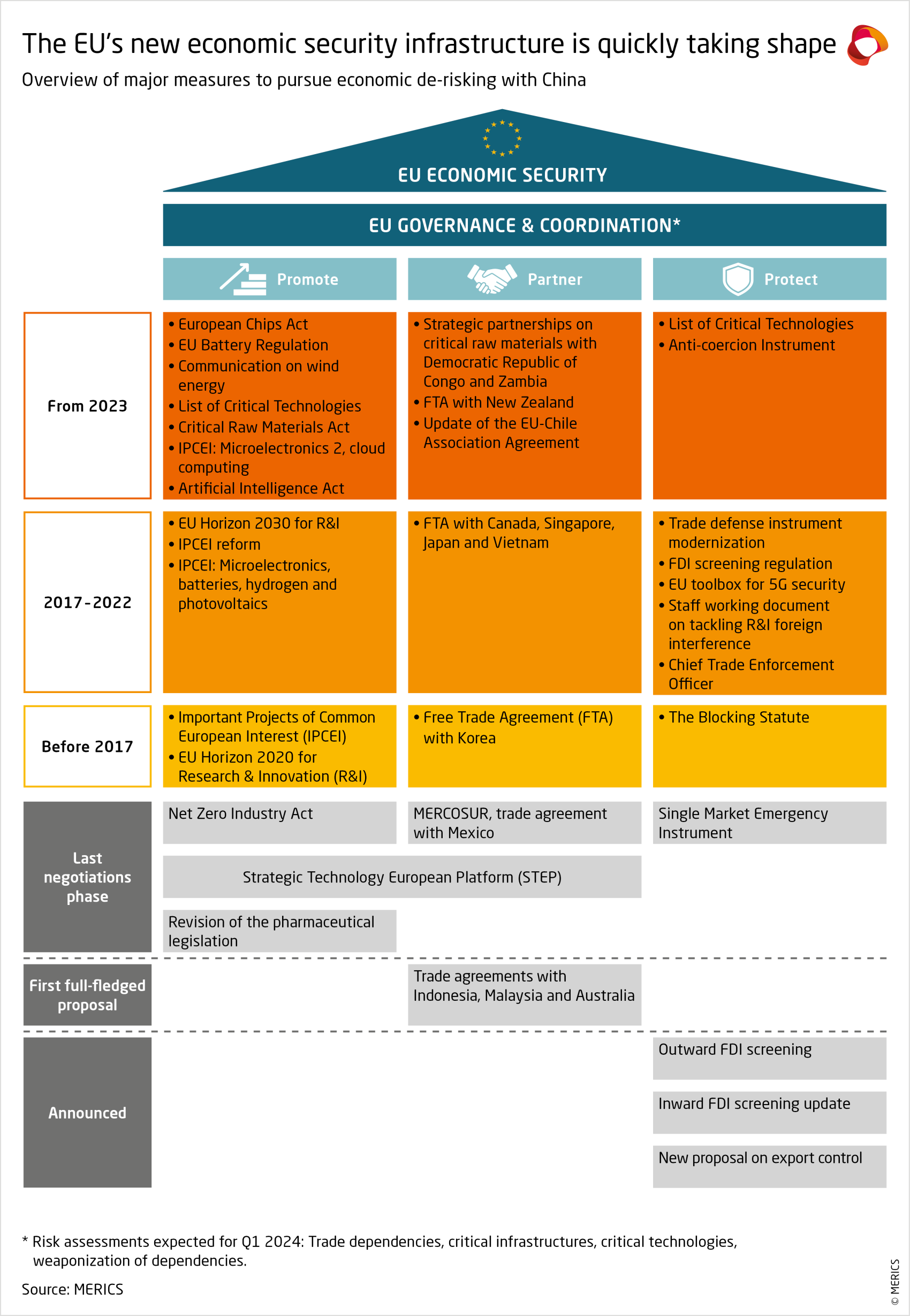

The Commission has suggested a broad range of measures, most of which are already finalized or well under way. These are organized into those which promote EU capacities, those which protect them and those on partnering with third countries to do either. Although formally country-agnostic, China looms large as the country on which the EU perceives it has the most dependencies, and which also happens to be a massive investor in infrastructure worldwide while being an active practitioner of cyberattacks, technology theft and economic coercion.

An intensification of the flow of instruments and measures

The finalization of measures has gained pace since the end of 2022 (see figure 1). An Anti-Coercion Instrument, agreed after years of discussion, aims to deter economic coercion, a practice with which China is very familiar. The more flexible EU export controls framework enables new types of products to be covered, as in the recent case of Dutch restrictions on sending semiconductor machinery to China. The new International Procurement Instrument (IPI) and the Foreign Subsidy Regulations complement the EU’s arsenal for protecting domestic interests against China, a country that stands out for its closed-off public procurement and massive state subsidies.

Targeted measures have also been rolled out for critical sectors, which largely overlap with China’s own priorities. The planned Strategic Technology European Platform (STEP) is intended to serve as a tool for leveraging more public funding to support critical sectors. It will come on top of recent IPCEIs on chips, solar panels and cloud services. The EU has also finalized the Critical Raw Material Act, which aims to diversify supply chains and develop domestic capacities, something which the Net-Zero Industry Act should soon also do further down the value-chain for green industries.

A list of critical technologies has been established. Chips, artificial intelligence, and quantum and biotechnologies have become priority areas for risk assessment and future policy remedies. The list also targets partners that pose “risk of civil and military fusion”, de facto putting China front and centre.

The long road towards implementation in the EU

This impressive list of tools and instruments is still to be implemented. Public policy conceptions and roll out take time, especially in the EU. The impact of industrial policies sometimes takes years or even decades to become apparent.

There are also more political reasons for the slow implementation of measures. Implementation has much higher costs than policy conception. Brussels is faced with tight budget constraints and most of the new measures have not resulted in the creation of administrative roles to put concepts into practice.

Fear of retaliation by China may be another reason for slow implementation, especially among member states. The recent EU-China summit of December 2023 and the launch of an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric vehicles were designed by the Commission to make clear that a more assertive implementation of the EU level-playing-field toolbox on Chinese products might be around the corner. There is a shared view among European investigators and decision makers of the need to avoid a repeat of the solar panel case in the previous decade, when fear of retaliation delayed investigations until the European industry had been almost wiped out by cheaper Chinese competitors. Tellingly, the EV investigations have already generated discomfort in some European capitals and industries, apparently out of fear of losing market access to China. This discomfort appears justified as China has opened an anti-dumping investigation of its own into French wine and spirits, which looks like the expected retaliatory move.

The other slow-moving front of the de-risking agenda is partnering with like-minded countries. In July 2023, the EU approved a trade deal with New Zealand – the first in four years. Another just concluded with Chile includes innovative provisions on guaranteeing better access to minerals there. New types of partnership have also been established with eight partners to secure Europe’s supply of minerals. Discussions are advanced within the G7 and among like-minded countries to develop partnerships related to China de-risking topics, be it on anti-coercion, supply-chain securitization standards and approaches, AI or securing trade routes and critical supplies.

Overall, these appear more limited than the set of de-risking measures to protect and promote critical European sectors, and with good reason. Partnering before you have your own house in order is putting the cart before the horse. Besides, Europeans have not devised a common view on who to partner with. Partnering often means some form of constraint on autonomy, something which Europeans often struggle to agree on. Typically, a coalition against economic coercion would require some commitment to collective action if a partner were to be subject to such attacks.

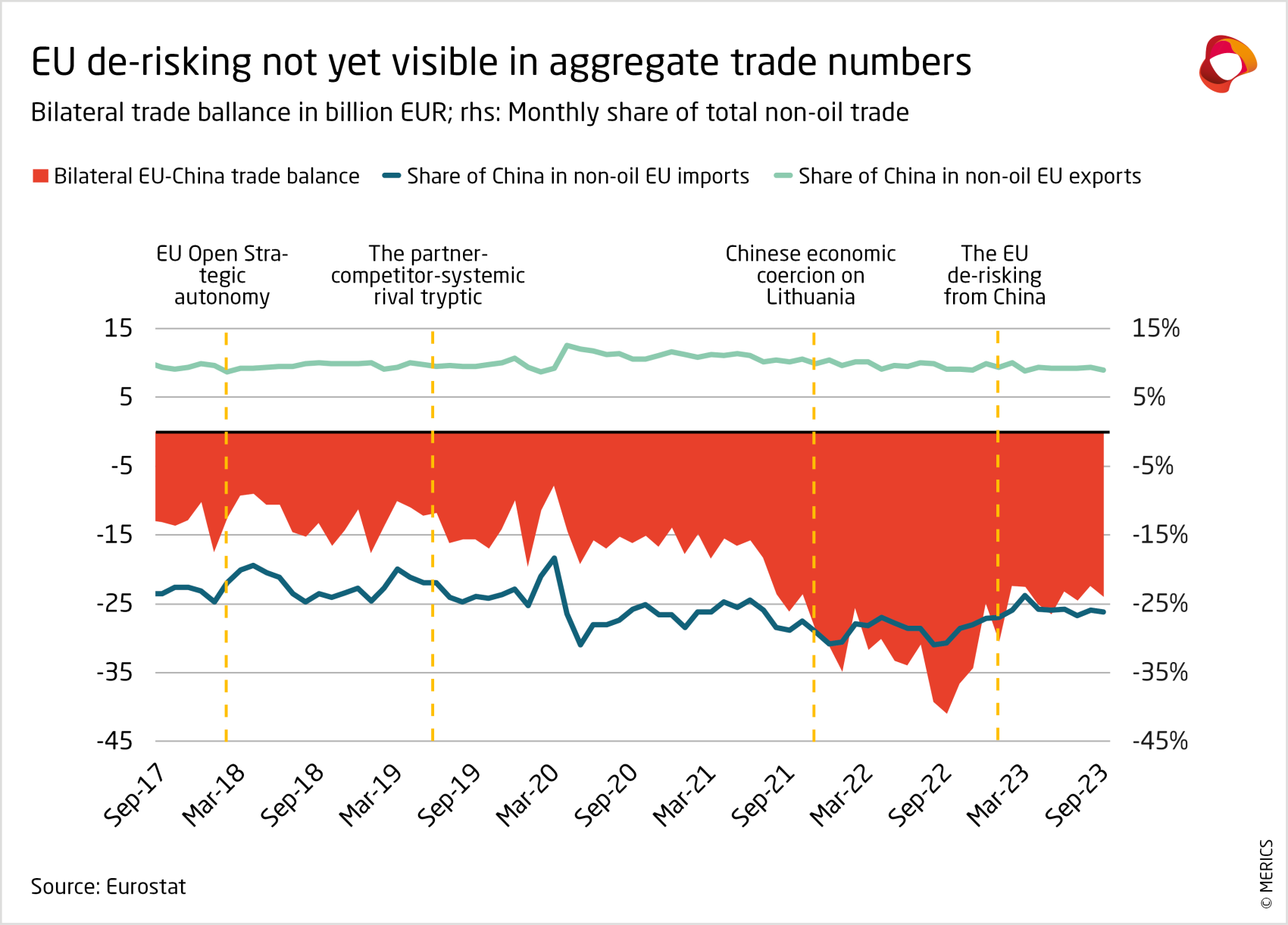

This slower implementation might explain the increased sense of disconnect between the political discussion in Europe and the economic reality on the ground. Indeed, the aggregate numbers on Sino- European economic relations do not indicate a clear break (see Figure 2). On the other hand, new policy directives take time to have an impact, especially where complex value chains are involved. The targeted nature of EU de-risking ambitions caps the magnitude of the impact at the macro level. However, discussions are still needed on how exactly de-risking needs to happen across critical sectors intertwined with China, and serious conversations lay ahead.

The European Council is set to lead in-depth discussions

While the Commission appears decided on pushing its de-risking agenda vis-à-vis China, some member states have diverging views – a fact that might also postpone implementation as this often depends on the member states. The same holds for decisions on and modalities for partnering with third parties. The resources that need to be put into the new instruments in order for them to work will also be a matter for the member states’ budgetary negotiations.

Member states share a tendency to demand more action at the EU level, hoping to leverage the size of the Union and avoid coming under fire themselves. At the same time, however, they tend to be extremely reluctant to give the EU institutions more power to act on their behalf.

Given the geopolitical challenges ahead, more fundamental discussions are needed. However, de-risking overlaps with national security considerations, where the EU level has limited leeway. The discussion on export controls encapsulates such tensions. Measures at the national level make only limited sense, given the technological capacity and bargaining power of member states compared to the US or China. At the same time, the Europeanization of export control measures, which could take many forms, is a red line for some member states as it interferes in their foreign and security policies.

Another dimension that also questions member states’ willingness to properly develop a more geo-economically forceful EU is governance. The separation of trade, economic and foreign affairs within the complicated European decision-making machinery does not lend itself to a consistent and proactive approach to multidimensional objectives such as economic security.

The upcoming risk assessments and a more structured framework for exchanges will fuel more constructive discussions on de-risking. The European elections and a new mandate for the Commission will also provide the right window of opportunity for in-depth conversations on more fundamental topics, such as the budget and prerogatives, that pertain to a broader discussion on the future of the EU.

You were reading the EU chapter from the ETNC Report 2024 "National Perspectives on Europe’s de-risking from China". Go back to the main page.