Europe's Connectivity Agenda + Semiconductor supply chains + Cyber weaknesses

Story of the month: The EU’s new connectivity agenda – What (not) to learn from Belt and Road Initiative?

by Jacob Mardell and Grzegorz Stec

The Council of the European Union recently approved conclusions on “A Globally Connected Europe.” The adoption of this policy document is the latest milestone in an ongoing European attempt to orchestrate a new connectivity strategy, partly in response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In 2018, an EU joint communication on “Connecting Europe and Asia” was released, establishing the building blocks for a “sustainable, comprehensive and rules-based” connectivity strategy. Over the past year, the topic of connectivity has picked up steam, with European Parliament urging a global connectivity strategy, the adoption of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy with connectivity elements and G7 discussions about a new “build back better world” initiative.

Although the Council conclusions themselves make no reference to China, competition with China provides the context for a renewed connectivity agenda. Implicit in the calls for a new strategy is the acknowledgement that China is doing something through the BRI that warrants a course adjustment from the EU.

The EU is not new to the connectivity game – but it has an image problem

The EU, which is home to world’s largest multilateral development bank (the European Investment Bank), has been building connective infrastructure across the world for decades According to data from the European External Action Service, EU development assistance between 2013 and 2018 stood at EUR 414 billion, slightly lower than EUR 434 billion of Chinese financing for BRI projects. A bigger difference between these two figures is that the EU money came in grant form, while China extended theirs as loans.

The Council’s conclusions acknowledge that despite this economic reality, the EU is failing to reap the reputational rewards of its connectivity work. One of the several steps recommended by the Council conclusions to address this is to “ensure the visibility of the EU’s global connectivity actions through coherent strategic communication in a Team Europe approach.” The conclusions envisage a “unifying narrative” as well as a “recognizable brand name and logo.”

But the BRI’s appeal transcends branding, and its narrative success owes much to domestic and regional politics of host countries. In Serbia for instance, a pro-China agenda serves the political ambitions of the Serbian president – it is the Serbian media rather than the Chinese which is responsible for the BRI’s visibility.

The EU needs to cut red tape and make applications for financing easier

The relative convenience of Chinese finance is another part of the BRI’s appeal to host countries. Compared to EU funding, the BRI package comes with less red tape.

Although suboptimal in terms of market considerations, the tying of Chinese engineering contracts to state finance, which largely facilitates BRI, is sometimes more accessible for governments with limited resources. The application for Chinese finance for projects executed by companies with links to the party state is more of a political than bureaucratic process, relying on interpersonal ties and access to the Chinese embassy rather than administrative capacity.

The recommendation of the Council conclusions to “present coherent and streamlined financing schemes” may help address this problem. The establishment of the “Global Europe” fund, which unifies several EU external action instruments, appears to be a step in the right direction. However, the EU should be careful to make sure that such efforts go beyond branding and bureaucratic re-organization. It can ensure this by cutting red tape and making application processes clearer for recipient countries.

Regarding increasing accessibility of funds, the Council recommends mobilizing “the private sector to finance and implement projects.” Yet, persuading private investors to put capital into low short-term yield, high-risk infrastructure projects is the holy grail of development finance. The problem is a lack of bankable infrastructure projects, leading to a decline of private investment in developing country infrastructure by 36 percent over the past 10 years. The calls repeated in the Council conclusions for a “Business Advisory Group” for private-public consultation and coordination on projects is certainly an important step in this process.

BRI-style hard infrastructure projects are appealing for local elites

BRI also appeals to host countries because it facilitates often large-scale hard infrastructure projects that are unable to attract financing from status-quo international financial institutions because they are deemed too risky or otherwise unsustainable. For example, the Chinese financed controversial highway in Montenegro was first turned down by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development as commercially unviable.

Such projects are attractive to local elites because they are deemed necessary long-term investments for economic development, and/or because they provide kickbacks and political capital. A big bridge simply provides a better photo opportunity for the campaign trail than a cluster of small EU grants for private enterprise. If the EU were to put itself more often in the shoes of local elites and appreciate their political considerations, it could increase the appeal and impact of its connectivity schemes.

The Council conclusions call on the commission to “identify and implement a set of high impact and visible projects” as part of the new connectivity strategy, thus acknowledging a need for more physical infrastructure.

BRI’s successes and failures could inspire the EU

Just as the EU is gearing up to compete with BRI on the assumption of its success in creating economic leverage and generating political influence, there is evidence to suggest that the BRI as we know it – big loans for infrastructure projects – is in retreat. Although the specifics are contested, anecdotal evidence and data from Boston University show that policy bank loans from China peaked as early as 2016 and have been declining since.

Although it is often thought of in terms of strategic economic corridors, the reality of the BRI is that projects are rarely planned with network effects in mind. By deploying its expertise in connectivity and planning economic corridors that further EU strategic interests, the EU could achieve what the BRI set out but failed to do.

Framing the new connectivity strategy as a competition with China may be unnecessary. Neither does the EU need to ape the BRI. Instead, it should embark on its course correction taking BRI’s successes and failures as inspiration.

Read more:

- Council of the European Union: Council conclusions – A globally connected Europe

- European Parliament: Resolution on connectivity and EU-Asia relations

- Council of the European Union: Global Europe: final green light for the new financial instrument to support the EU's external action

- Rhodium Group: China’s Belt and Road: Down but not Out

- MERICS: Competing with China's Belt and Road Initiative

EU sets sights on semiconductor industry frontier – Finding balance between the US and China will not be easy

The European Commission is promoting development of more sections of the semiconductor supply chain in Europe and pushing for localized cutting-edge semiconductor manufacturing. At the same time, the Biden administration is increasingly seeking cooperation from Europe over semiconductor supply chain issues vis-a-vis China. As China is engaged in its own effort to upgrade along the semiconductor supply chain, technology transfer and competitiveness issues involving European and Chinese actors are growing in prominence. Increasing attention is being paid both to the Dutch manufacturing equipment leader ASML and to collaborations between Chinese actors and the Belgian-based R&D center IMEC.

Illustrating the increasingly politicized nature of policy in the semiconductor sector is the current debate in the UK over the purchase, by Dutch-based and Chinese-owned company Nexperia, of the Newport semiconductor manufacturing facility in the UK. Under political pressure, the British government has initiated a security review of the acquisition, with a view to the potential long-term implications of Chinese actors benefiting from the acquisition.

MERICS take: Semiconductors are a key element of the EU’s “Digital Compass” plans to build world-leading positions in digital economy sectors by 2030. EU officials are framing the need for Europe to develop local capacity in cutting-edge semiconductor manufacturing in both geopolitical and national security terms. However, European industry and expert commentators are skeptical about focusing on this step of the semiconductor supply chain, given the difficulty and expense of developing cutting-edge manufacturing. Many advocate instead for a focus on the existing niche strengths of European firms, or on chip design as a more accessible and profitable step in the supply chain.

Europe faces many challenges in attaining a larger share of the global semiconductor sector, given the complex nature of the technologies involved and growing external political pressures. China’s upgrading along the semiconductor supply chain raises prospects of increased competition for European firms and risks from technology transfer through research collaborations and corporate acquisitions. The US is promoting a coordinated approach among allied nations to maintain leadership and supply integrity vis-à-vis China in this critical technology.

But European firms are also competitors with companies in the US and US allies in East Asia. The goals of European “strategic autonomy” and “digital sovereignty” imply that policy for the semiconductor sector cannot only be defined by the requirements of allied cooperation against challenges from China. Finding the optimal balance will not be easy.

What to watch: The effectiveness of the new EU-US Trade and Technology Council will be a significant indicator of the potential for transatlantic cooperation vis-à-vis China in emerging technologies where European and US interests do not entirely converge. Simultaneously, the effectiveness of European industrial policy for semiconductors will depend heavily on responsiveness to actual industry conditions and the priorities of European companies.

Read more:

- FT: Semiconductors: Europe’s expensive plan to reach the top tier of chipmakers

- Total telecom: Intel plans $20bn ‘ecosystem-wide’ chip project in Europe

- WSJ: China wants a chip machine from the Dutch. The U.S. said no

- Bloomberg: The U.S.-China tech conflict front line goes through Belgium

- The Conversation: Semiconductors: Chinese takeover of UK’s leading chipmaker doesn’t need a security review – here’s why

- CNBC: The UK chip plant that’s being sold to a Chinese-owned firm has over a dozen contracts with the British government

- MERICS: Mapping China’s semiconductor ecosystem in global context: Strategic dimensions and conclusions

Like the EU, China grapples with its cyber weaknesses

The EU has joined Five Eyes countries and NATO in a coordinated effort to condemn Chinese state-sponsored cyberattacks. The EU statement published on July 19 announced that several recent attacks originated from China, including the sprawling Microsoft Exchange hack. Unlike partners, Brussels has not attributed the malicious cyber activities to the Chinese government. It did, however, name hacker groups APT 40 and 31 as responsible for IP theft and espionage. The groups are understood to have ties with the PRC Ministry of State Security.

Europe continues to be a target of espionage, IP theft, hacks and ransomware attacks from China, resulting in economic losses and negative spillovers for security, society and democratic institutions. In June 2020, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen publicly called out China for a series of cyberattacks aimed to steal Covid-19 related research. The bloc then imposed its first-ever sanctions against cyberattacks, targeting Chinese, Russian and North Korean hackers. China maintains that it is a victim, not a perpetrator, of cybercrime.

MERICS take: The Covid-19 pandemic pushed more economic, social and government activities online, giving countries a glimpse into the security vulnerabilities in the digital technologies they became reliant on. For the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) this is a top concern. On the one hand, China’s offensive cyber capabilities have progressively increased. President Xi Jinping turning China into a “cyber great power” (网络强国) a priority, marrying internet, industrial, technology and military policies to boost the economy and cement the CCP’s power at home and abroad.

On the other hand, these ambitions stem from a position of insecurity. The party regards China’s enduring cyber defense weaknesses as a threat to its rule. Given Xi’s bold plans for the development of the digital economy, boosting cyber defenses to secure networks and data is an urgent task. The ongoing crackdown on ride-hailing company Didi reveals the extent of authorities’ concerns about foreign actors getting their hands on China-originated data.

In June, China released a draft plan for developing its cybersecurity industry, a sector the government expects to be worth CNY 250 billion (EUR 33 billion) by 2023. Last week, regulators issued new rules for managing security vulnerabilities in network products, which inter alia demand that any Chinese or individual that discovers vulnerabilities report them to national authorities and for that information not to be shared with foreign third parties.

What to watch: The EU is also beefing up its defenses against cyber threats. Last month, the Commission outlined steps to build a Joint Cyber Unit to pool information and resources from the Union’s patchwork cybersecurity ecosystem. The hope is to finally build an “EU coordinated response to large-scale cyber incidents and crises.” China’s cyber weaknesses should not allow the Europeans to underestimate its capabilities, nor can they afford to ignore the threat that China poses. The new rules on network product vulnerabilities, for instance, may indicate Beijing’s intent to store information about zero-days (i.e., undisclosed computer soft/hardware vulnerabilities) and later exploit them for offensive cyber operations.

Read more:

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the PRC [CN]: Public consultation on the "Three-Year Action Plan for High-Quality Development of Cybersecurity Industry (2021-2023) (Draft for Comments)

- South China Morning Post: China drafts three-year plan to boost its cybersecurity industry amid increasing concerns for data safety

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Cyberspace Administration of China, Ministry of Public Security [CN]: Regulations on the management of security vulnerabilities in network products

- IISS: Cyber capabilities and national power: A net assessment

- The Wall Street Journal: In the new China, Didi’s data becomes a problem

- European Commission: EU cybersecurity: Commission proposes a joint cyber unit to step up response to large-scale security incidents

- MIT Technology Review: How China turned a prize-winning iPhone hack against the Uyghurs

On human rights, European companies are increasingly caught between legal and political compliance

The European Union’s imports from Xinjiang more than doubled over the first half of this year, despite concerns over the use of forced labor in the western Chinese region, according to calculations by the South China Morning Post.

Nonetheless, multinational companies which have production sites or suppliers in the region have been under increased scrutiny. On July 8, the British parliament's Foreign Affairs Committee published an in-depth report on Xinjiang, recommending more coordinated action. French prosecutors have also opened investigations into allegations of forced labor in Xinjiang.

European companies, such as Volkswagen and BASF, have stated that they do their best to audit their factories and immediate suppliers, but some have also reported limits in implementing due diligence for downstream suppliers. Fortune magazine has reported that several US companies, including Patagonia, have adjusted their supply chains due to challenges of ensuring independent and comprehensive audits in the region.

The Chinese government seeks to dispel international concerns over human rights violations and forced labor. On July 8, China's Ministry of Commerce announced that representatives of international industry bodies and foreign firms in China will visit Xinjiang soon. But the ministry spokesman also referred to allegations of forced labor as “lies” that served as a means of “protectionism.”

MERICS take: While signaling openness it is also clear that Beijing demands political compliance. The Chinese government is trying to win over companies, including major European businesses, as advocates for the official position. The ministry spokesman said that more firms and organizations will “respect facts” and “conform to the law of the market.”

This could mean trouble for companies that comply with US and EU sanctions or take a more vocal stand on implementing human rights due diligence. H&M was one of several companies faced with Chinese consumer boycotts since March and the new Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law provides the China’s leadership with an additional tool to penalize foreign actors.

What to watch: In recent months, a growing number of European parliaments have debated a categorization of human rights abuses in Xinjiang as genocide or crimes against humanity. Beyond targeted action on forced labor in Xinjiang, the broader regulatory environment in Europe is changing. Countries such as France, Germany and Norway have already passed supply chain legislation requiring human rights due diligence. With a European Due Diligence Act in the works companies will be hard pressed to be both legally compliant with European norms and politically compliant with China’s official position.

Read more:

- SCMP: Xinjiang’s exports to the EU boom, despite political concerns over forced labour

- Euronews: China hits back against damning report by UK Foreign Affairs Committee on Xinjiang "atrocities"

- BBC: France investigates retailers over China forced labour claims

- Global Times: Reps from intl institutions and multinational companies to visit Xinjiang

- Fortune: Reports of forced labor are driving brands to abandon Chinese cotton

- Handelsblatt [DE]: "Don't leave me hanging": How German companies do business in China's oppressed Xinjiang province

- MERICS: China’s Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law: A warning to the world

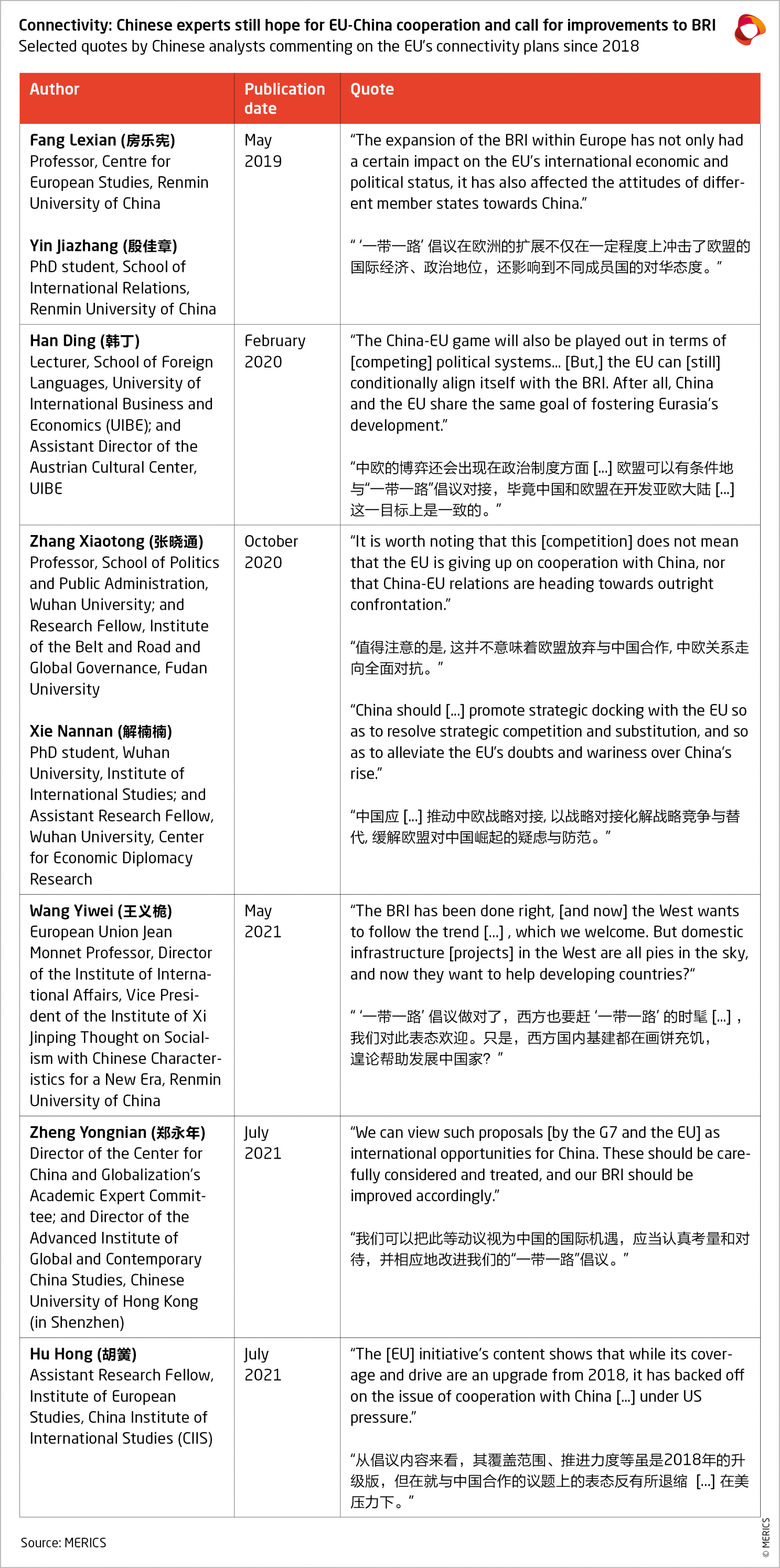

Paper tiger with dangerous friends: How Chinese experts view the EU’s renewed connectivity push

by Thomas des Garets Geddes and Grzegorz Stec

The EU Council’s proposed connectivity update garnered relatively few reactions among China’s intellectual elites. Nevertheless, Chinese assessments of this potential update are noteworthy and remain, by and large, in line with those that followed Brussels’ previous connectivity strategy three years earlier. In other words: (i) China will believe it when it sees it, (ii) EU-China competition does not preclude strategic alignment and increased bilateral cooperation. Here, we discuss some of the main themes that have emerged from these discussions since 2018.

EU motives as viewed from China

As was already the case three years ago, Chinese experts interpret the EU’s connectivity plans primarily as a reaction to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and to its vaunted successes. Brussels is depicted as trying to protect its economic and political interests against Beijing’s spreading influence across the world. Many suspect that China’s supposed inroads into Central and Eastern Europe are at least partly behind these new plans. Although some cite the US’s influence over this proposed update of the EU’s connectivity strategy, one analyst insists that it should also be viewed in light of Europe’s growing strategic autonomy. Moving beyond the EU’s defensive stance, two academics describe a nascent “geopolitical Europe” (“地缘政治欧洲”) adapting to a world of power politics and increasingly prepared to wield its economic power to achieve its goals.

The EU’s strategy: “a paper tiger”

But however determined the EU may be in this renewed connectivity push, analysts in China are highly skeptical about how it will manage to implement these plans. The EU, they argue, is currently too weak, both economically and politically. They simply do not believe that Brussels will be able to marshal the necessary financial firepower to compete with Beijing. On the one hand, they highlight the EU’s lack of economic growth and its recent “loss of the UK.” On the other, they point to the differing geopolitical interests and easily exploitable divisions among EU member states. But EU “weaknesses” are also found in the Commission’s values-based foreign policy, they believe. Many emphasize the alleged unease of developing countries over the EU’s insistence on attaching political conditions to its development aid and infrastructure investments. China understands the needs of the developing world better, they say.

How China should respond

Despite such supreme confidence, similar fears to those described in last month’s briefing, do occasionally transpire. In other words, this section of the Chinese elite has become increasingly worried about the growing pushback against China in the EU and the potential for an “anti-China” coalition. To stave off this threat, Beijing should find ways of strengthening its ties with Brussels and of improving the BRI’s image, many argue.

For all its alleged weaknesses, the EU’s sustainable and rules-based approach to connectivity is often seen as a model to emulate (at least some parts of it are). Although never explicit in their criticisms of the BRI, Chinese experts do suggest possible improvements including reducing the risk of certain projects being labelled as “debt-trap diplomacy,” gradually decreasing the involvement of Chinese state-owned enterprises, increasing the involvement of foreign companies and workers, and promoting more environmentally friendly projects.

Our take: What this means for the EU

Considering these Chinese experts’ views, the EU’s renewed connectivity initiative may provide Beijing with additional stimulus to adopt higher standards for its BRI projects. However, it is also likely that connectivity initiatives will increasingly become a source of tensions in EU-China relations.

Despite the EU’s diplomatic efforts to frame its connectivity plans as inclusive, Beijing is likely to view the bloc’s efforts to cooperate with like-minded countries with the aim of upholding a system that supports rules-based market economies, as aimed against it. Especially so, should the EU indeed explore joint connectivity work with the United States as indicated in the Council’s conclusions. Consequently, in the short to medium term, Brussels may find itself with fewer and fewer avenues to pursue connectivity cooperation with China as politics surrounding connectivity increasingly take center stage.

Read more:

- Academic article by Fang Lexian and Yin Jiazhang [CN]: Connecting Europe & Asia – The EU's Strategy and What it Means for China-EU Relations (Quote 1)

- Academic article by Han Ding [CN]: The EU's New Asia Strategy and the Belt and Road Initiative (Quote 2)

- Academic article by Zhang Xiaotong and Xie Nannan [CN]: "Geopolitical Europe" - The Geopolitical turn of EU power (Quote 3)

- Global Times op-ed by Wang Yiwei [CN]: What the West's rush to hedge against the BRI means (Quote 4)

- PP commentary by Zheng Yongnian [CN]: Is the West capable of implementing its alternative-to-the-BRI plans? (Quote 5)

- China Internet Information Center op-ed by Hu Hong [CN]: The EU needs to engage in global connectivity with a calm and pragmatic mindset (Quote 6)