China sets hopes on blockchain to close cyber security gaps

With an already large and growing digital economy and increasing use of the Internet of Things (IoT), China is in dire need of strong data security standards, data privacy protection and an efficient digital infrastructure. Kai von Carnap looks at how China is deploying blockchain technology to meet these challenges and analyzes both its rate of success and the implications China’s approach has for other parts of the world, including Europe. His analysis is accompanied by a slidedeck that provides context for and deeper insights on China’s attempts to develop and control this strategic technology.

Every three months China’s population with access to the Internet increases by the size of a medium-sized EU country. By February 2021, it had already reached a staggering one billion people. At the same time, its cyber security issues are growing too. In January 2020, for example, 200 million phone numbers were lost by China Telecom (中国电信), one of China’s three telecom SOEs. A month later, 538 million leaked accounts on Weibo, a microblogging platform often compared to Twitter, were found on the dark web - a worrying number, given that only 500 million users are active on the platform every month. Reporting on these security breaches and on a 4.4-fold increase in malware-hosting websites, CCID, a Chinese ministry-led think tank that specializes in the development of information industries, said recently that it was “not optimistic” about the state of China’s overall cybersecurity.

In recognition of its growing cyber vulnerabilities, the CCP is giving increasing support to the development of blockchain technology. Widely known as the technology behind cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, China hopes that this emerging technology – also known as Decentralized Ledger Technology, or DLT – will enable it to ramp up the resilience of its digital infrastructure and make full use of the efficiency potential of its digital economy (Slide 2).

Blockchain technology has various advantages over conventional information systems and can be applied to strengthen backend digital infrastructure – like putting iron cladding around leaking pipes. Moving away from centralized towards distributed data structures generally improves network security, which is why the IEEE is calling it “one of the most secure technologies in the world”. However, it comes with new vulnerabilities, some of which are inherent to the technology and others that are being created, inadvertently, by the CCP itself.

From unchained instability to on-chain security

Prior to latest events, China’s grassroots blockchain industry had been developing rapidly for several years. However, increasingly restrictive ad-hoc regulations were causing widespread regulatory uncertainty and there were pan-industry calls for policy normalization. Then in October 2019 President Xi Jinping made an announcement that set a new direction – one that would shift the focus of activity from cryptocurrencies and initiate a flurry of new blockchain development centered around self-reliance and cyber security. As a result, blockchain development in China today is driven primarily by the needs of government services and by projects controlled by corporates or private consortia.

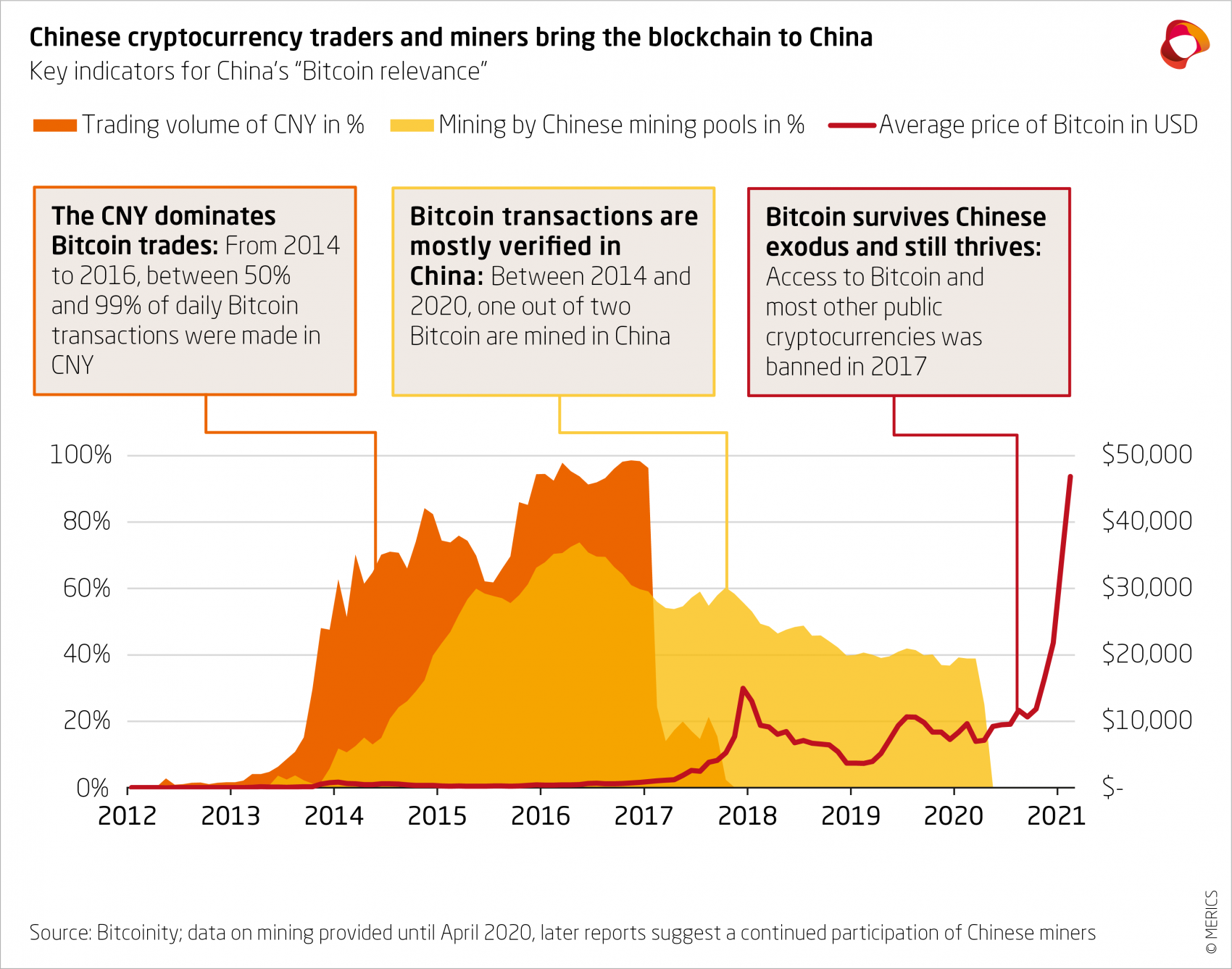

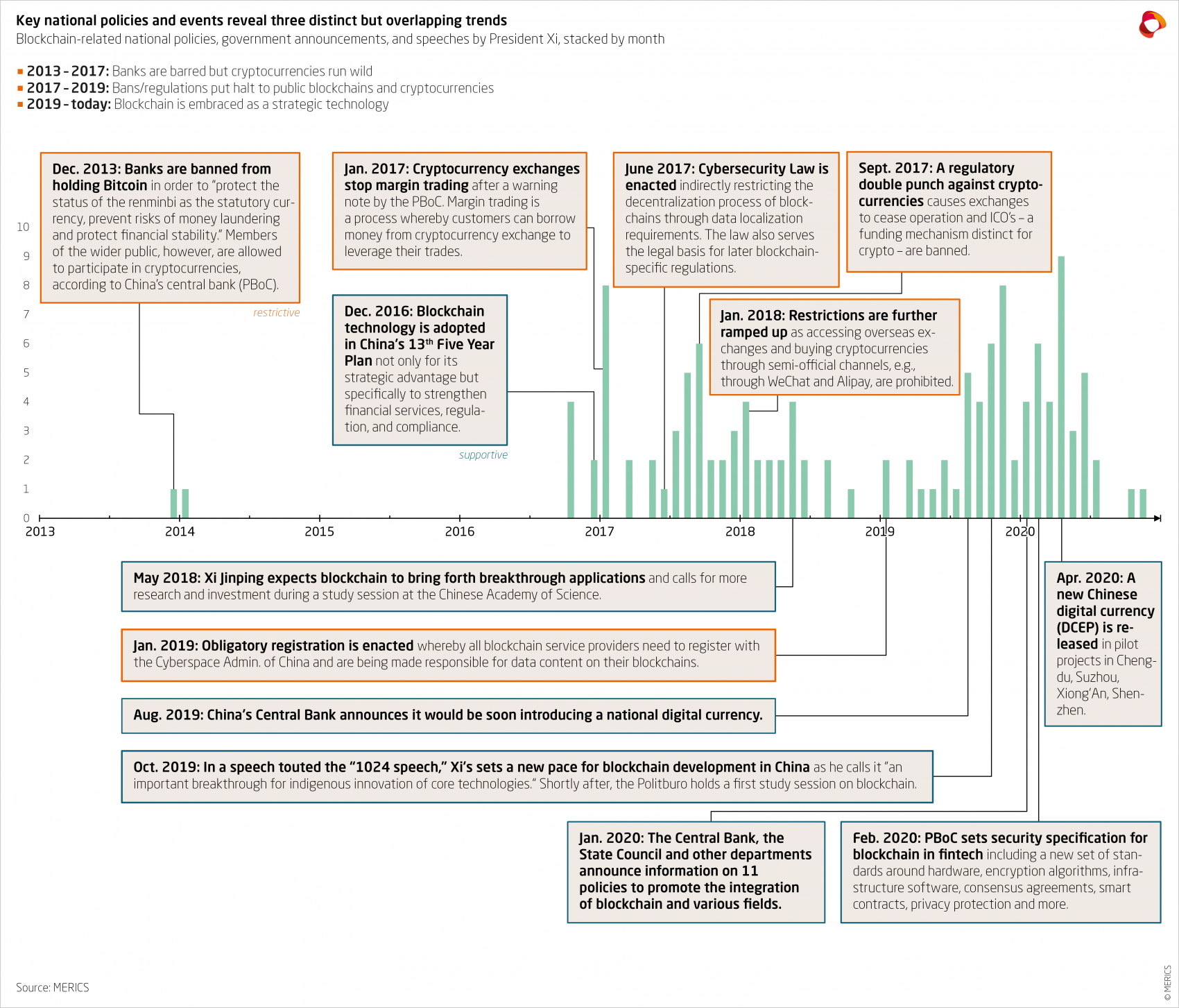

The relationship between DLT and China’s party state, society and industry is complex and has been formed in three distinct yet fluidly transitioning phases. The four years from 2013 to 2017 were the heyday of small private investors, developers and founders in China, who focused on cryptocurrencies and public blockchains.

Demand for cryptocurrencies was driven by a variety of factors, lead by the fact that people saw their incomes rapidly rising but faced strict capital controls and had few investment options. Largely ignored by political elites, the CNY quickly dominated cryptocurrency trades. Even Baidu accepted Bitcoin, albeit briefly. Chinese startups founded during this time were embedded within the international blockchain ecosystem community. Many are still in key positions in the cryptocurrency industry today, such as the world’s biggest mining equipment producer (Bitmain), the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange (Binance) and some of the most valuable Chinese cryptocurrencies (VeChain, Neo).

During the second phase, from 2017 to 2019, growth in what had been an unregulated industry came to a halt. Because outflowing CNY escaped supervision by the state, and the extent of fraudulent crypto schemes was worryingly unknown, in September 2017 China’s Central Bank, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, and other regulatory bodies banned trading in cryptocurrencies and many cryptocurrency exchanges were closed down overnight.

Perhaps most impactful was the ban on so-called Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), a distinct blockchain funding mechanism that “seriously disrupted the economic and financial order” in the eyes of China’s central bank. As a result, many Chinese blockchain startups moved abroad, but this period also saw China’s tech giants enter the industry, launching private non-cryptocurrency blockchains. One such example is Baidu’s own Xuperchain.

On 24 October 2019 President Xi Jinping’s speech ushered in the third phase, integrating the development of blockchain technology into the party-state’s long term strategic goals. In what is now known as the “1024 speech”, Xi said that blockchain ought to be seen as “an important breakthrough for indigenous innovation of core technologies” (核心技术自主创新的重要突破口). The policy jargon not only reflected an unprecedented rhetorical embrace of the technology per se but also indicated the role it would play in achieving strategic goals.

Framing blockchain as “indigenous innovation” rendered it as a means to achieving technological self-reliance. As Xi said in 2016, it was the lack of technological self-reliance that had prevented China from becoming an "Internet Great Power" (网络强国).

Developing “indigenous innovation” was therefore key to reducing China’s dependence on foreign technology and to addressing an insufficiency in “core technologies” (核心技术) and cybersecurity capabilities. “While others use planes and guns, we’re stuck with big swords and spears,” he said. This message was underscored in 2018 when Xi said that China was short of “core technologies” (核心技术) to ensure national and cybersecurity and that “breakthroughs” (突破) were needed.

City governments and other agencies adopt DLT

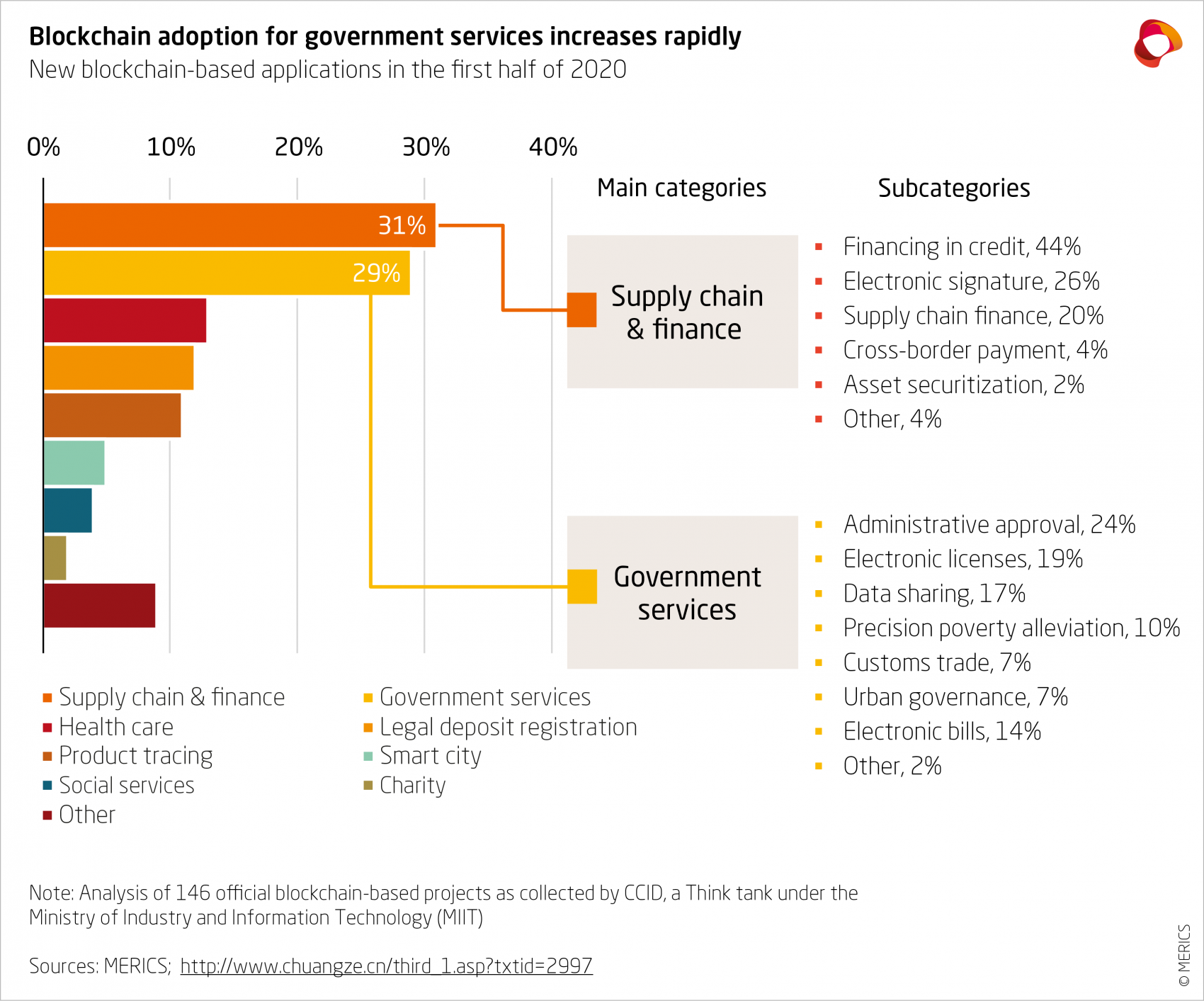

Since Xi’s speech, the integration of blockchain-based services, particularly by provincial and district governments, has accelerated and the technology is becoming a key pillar of cyber security. As of 2020, blockchain applications for government services represented more than one fourth of all blockchain applications developed in China, and many of the 400 or more policies published by national ministries as well as provincial and city governments support this development (for further details see Slide 7 and 9).

The city government of Jiangmen, a city of five million bordering Macau, for example, set out the case: “Originally blockchain technology was designed for cryptocurrency, but now we can see that it has great potential in many fields, especially in cyber security, because it can be used to prevent cyber attacks, leaks, identity theft or malicious transactions.” In the statement, city officials explained further that DLT can improve cyber security in multiple ways, by stricter identity authentication, improved data attributes and flows, and more advanced record management systems at the fringes of IoT and Industrial IoT.

The first blockchain services enabling cross-provincial and cross-departmental data exchange are already operational. Hangzhou, for example, launched a blockchain-based platform in 2018 for its internet court, verifying two billion transactions within months. That blockchain network soon after expanded to a larger DLT-based platform called LegalXChain, established by the “Alliance Chain Data Communication Internet Court”.

The Hangzhou court is one of 22 prosecutorial institutions on the LegalXChain, including the Beijing and the Guangzhou Internet Courts, as well as administrative agencies, legal enforcement agencies and notaries. Through this partial decentralization of the database, the technology is used to exchange and process cross-regional and cross-departmental data securely.

Seeking efficiencies in data management

Through merging civil databases DLT is also being used in an effort to make government services more efficient, for example by merging data to streamline the processing of personal data. In April 2020 the Haidian district in Beijing, which is home to China’s number one tech hub Zhongguancun and to China’s biggest blockchain industrial development park, created a local blockchain to verify and store documents related to government services – 1,621 in total – making the submission of paper copies unnecessary.

According to deputy director Hu Yuguo, personal identification and data verification can be extrapolated in real-time from the “One Network Portal” (一网通办). The district government claims that national, municipal and district-level data, including business licenses, marriage information, information on disabled persons, and patent certificate information can all be collected on the system.

Haidian has also merged a plethora of data relating to individuals provided by the Ministry of Education and the Civil Affairs Bureau, including ID card information, residence permits, marriage and divorce certificates, electronic business licenses, tax credit rating information, environmental assessment information, medical institutions’ licensing, housing qualification information, and more. Two months later, the city government of Beijing revealed plans to expand such blockchain-based government services for cross-border trade and enterprise banking.

Few other governments around the world have made more efforts to support the integration of blockchain technology than China’s. From fighting the “Three Critical Battles” (三大攻坚战) of financial risks, poverty alleviation and pollution, to the “Action Plan for Industrial Internet Development (2018-2020)”, China is seeking to leverage the technology for various high-profile policy initiatives.

At the “2020 Beijing Cyber Security Conference and Blockchain Security Forum”, the emphasis was on implementing DLT to strengthen China’s overall cyber security standard rather than improving traditional security protection systems. National security researchers and industry representatives praised DLT for its security capabilities and claimed that it could be used to support the legitimate transfer of government data. In the eyes of the CCID, “Blockchain solves crucial bottleneck issues of traditional digitalization around data sharing responsibilities, access authentication and privacy protection.”

The attempt to leverage DLT’s capabilities reopens old vulnerabilities

While the adoption of blockchain by various government bodies may be promising in terms of preventing data leaks and privacy breaches, the technology comes with a new set of cybersecurity vulnerabilities around access management and immature cryptography. Additionally, China’s attempts to regulate blockchains developed by the private sector can be counterproductive, undermining some of the core functions of the technology.

The “Blockchain Information Service Management Regulation” (区块链信息服务管理规定) is the best example of this (see full translation). Passed in January 2019, it effectively means that data stored on non-government blockchains is exposed to some conventional cyber security threats. The regulation stipulates that all Chinese blockchain projects must be filed with the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), an institution set up in 2013 to improve China’s cyber security standards. The CAC not only sets requirements that have to be complied with, it also supervises and inspects companies and the services they provide.

First, the regulation makes companies responsible for the data stored on their blockchains, requiring service providers to record and store user data for up to six months. This removes anonymity and lifts the possibility of only temporary right to access personal data. Second, companies are required to ensure that content stored on their blockchain does not “endanger national security, disturb social order, or infringe the lawful rights and interests of others”. However, these terms are not precisely defined creating legal uncertainty for companies seeking to comply with the rules.

The requirement nonetheless means that companies themselves must be able to inspect, review and potentially alter data stored on DLT in case of violations. Some companies, like Alibaba, have already developed a patent for “administrative intervention” to do so. Third, service providers must register their products, including future updates, with the CAC. Apart from potentially creating severe bottlenecks when there is a high update frequency, the regulation thus creates the threat of constant control over projects that have been filed with it.

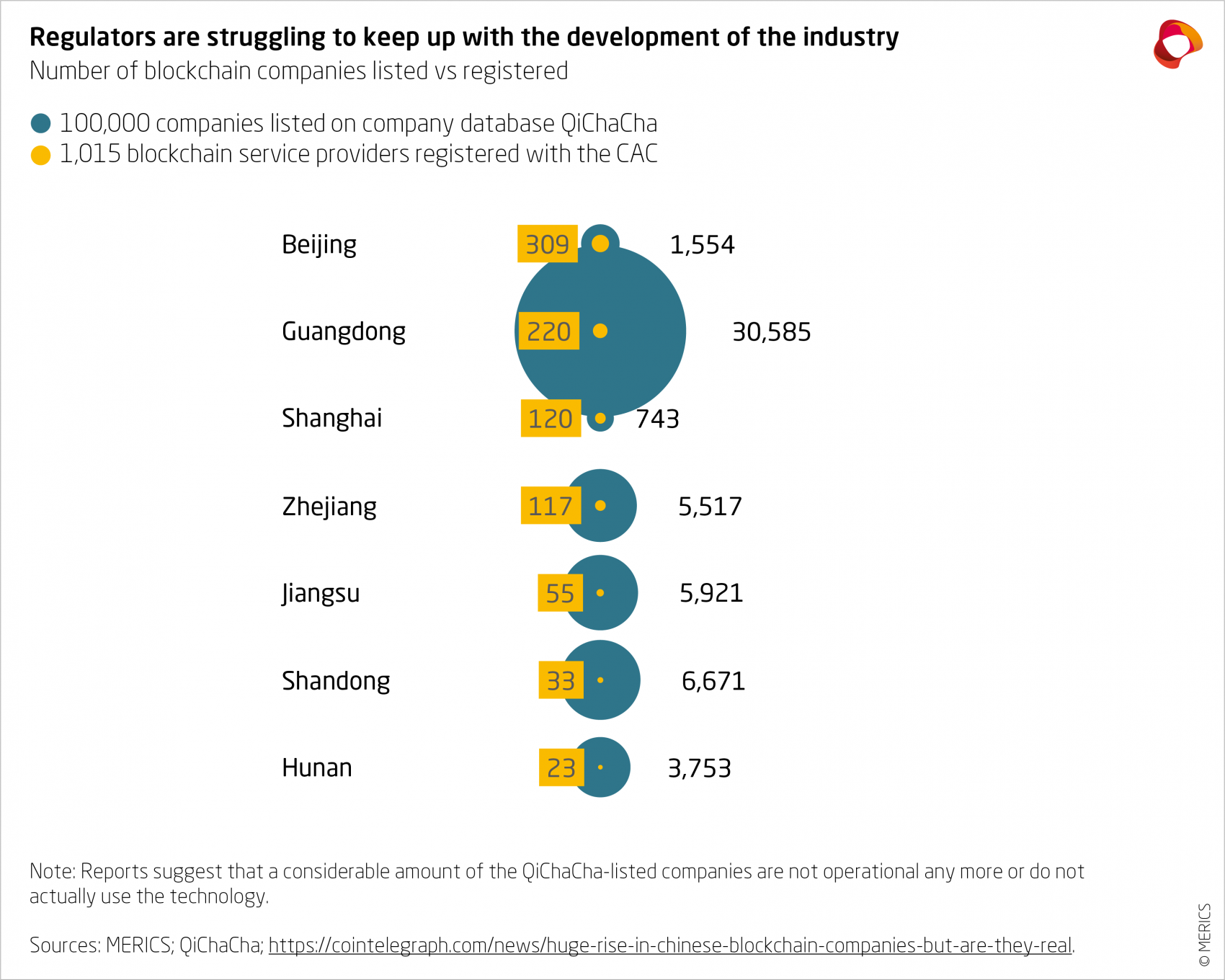

As of February 2020, a total of 1,015 projects, including VeChain and Baidu’s Xuperchain, had filed with the CAC, according to published entity lists (境内区块链信息服务备案清单). So far, this group only represents a fraction of all registered blockchain companies in China.

However, the requirement to provide user data or specifics about the algorithmic mechanisms to the CAC creates a dilemma for registered companies and undermines the benefits of a supposedly decentralized system. Given the high degree of accountability they face and the requirement to introduce technical means of artificial intervention, companies involved in such projects will have a hard time ensuring the independent integrity of their products – and that’s to say nothing of the fact that information such as user data and protocol details must be available to be handed over to the CAC whenever requested.

Furthermore, with a remit to oversee the whole sector, including updates, the CAC reintroduces the very concept that DLT was designed to get away from – the central point of failure.

Learnings and challenges for the global IT industry

The impact of further DLT adoption on China's performance as a cyber power is not trivial. Until recently, it has been argued that blockchain, through its libertarian nature, would make it more challenging for China to exert its cyber sovereignty. But through partial decentralization and the merging of different government datasets, China is in fact gaining more legally enforceable authority in its cyberspace while at the same time eliminating some of the conventional cyber vulnerabilities.

On the other hand, the dispersion of data ownership across different Chinese ministries and other government bodies (a product of merging and partial decentralization) creates new obstacles for cross-border digital information exchange.

Currently, there is the unresolved contradiction that arises if a Chinese blockchain wants to interoperate with another non-Chinese blockchain. In particular, the requirement for data localization, as stipulated by the Chinese Cybersecurity Law, currently leaves no room for communication with international public blockchains or blockchains from jurisdictions with similar requirements.

One potential answer is to separate Chinese blockchains that communicate internally from those that communicate externally. The Blockchain Service Network, a state-led digital infrastructure project, has already been set the task of doing so after there was disagreement over interoperability. China’s blockchain will now be separated into BSN-China and BSN-International – a solution that is in line with the new geopolitical strategy of “dual circulation”.

- Endnotes

-

1 “Indigenous innovation” (自主创新), sometimes translated as “independent innovation”, is a term that has been part of high-level political vocabulary since the 1990s.