Financial hub at risk

How China's reaction to protests jeopardizes Hong Kong's status

Main findings and conclusions

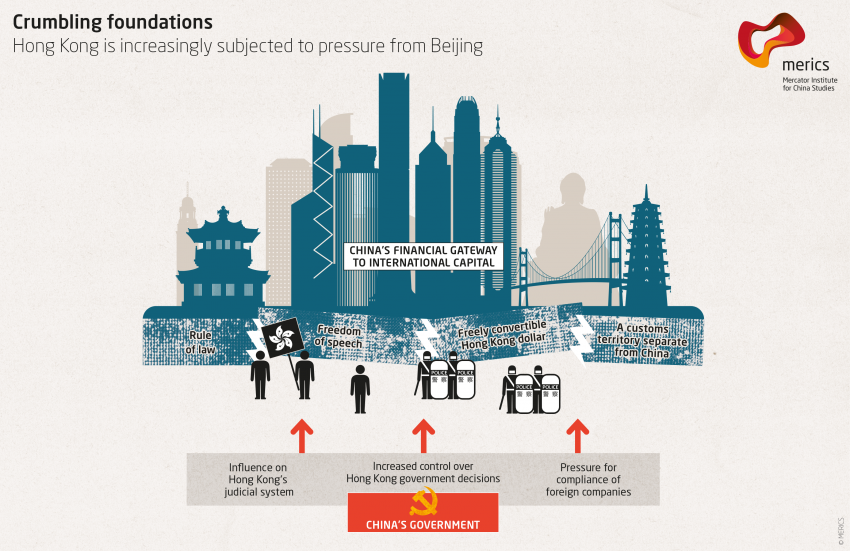

- Hong Kong's position as a financial hub rests on the city’s high degree of autonomy. The city’s Special Administrative Region status has given Hong Kong the autonomy to fulfill the institutional requirements of an international finance and trading hub. Hong Kong’s freedoms, primarily the rule of law and a lack of capital controls, are essential for China to satisfy its growing appetite for international capital.

- Hong Kong is a vital gateway connecting China with global financial markets. The city has no real domestic competitors for this role, despite the growing importance of China’s financial centers. Hong Kong provides access to foreign currency and has a crucial role in integrating China’s financial system with global markets.

- Alternative offshore centers in Macau, Singapore or London can only serve as complimentary hubs. Other cities outside of the mainland come with considerable political and economic constraints for China. However, strengthening other offshore centers could contribute to an erosion and atomization of Hong Kong’s gateway function.

- Protests have hit Hong Kong’s economy, but its financial markets remain unaffected for now. The city’s function as an offshore financial center has so far not been affected. There has been no massive capital outflow, and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange continues to attract major IPOs. However, the city's ability to attract new companies and global talent has suffered.

- Growing distrust in Hong Kong’s institutions jeopardizes its position as an offshore financial center. Beijing’s hardline reaction threatens to inflict substantial and irreparable damage on the city’s institutions. The pressure for accelerated convergence with China’s political and legal system has reached a critical point.

1. China’s push to integrate Hong Kong politically jeopardizes the financial gateway

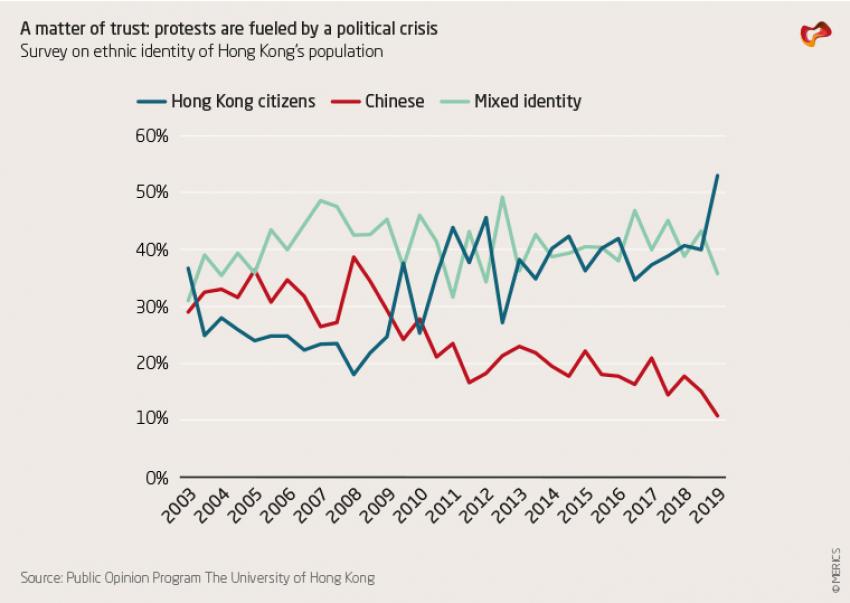

The political crisis that has gripped Hong Kong since March 2019 is far from any resolution and has the potential to hasten the city’s demise as an international financial center. The protests were ignited by a proposed extradition law (since dropped) which would have allowed extradition to mainland China, trial by mainland courts, and asset freezes in Hong Kong based solely on Chinese court rulings.1 The resistance by large parts of the population and business community expresses their distrust of China’s political system. Since 2008, the share of Hong Kong’s population identifying as Chinese has declined overall, with a further steep drop in 2019 (see exhibit 1). District council elections in late November in which pro-democracy candidates won a landslide 390 out of 452 seats on a record 71.2 percent voter turnout, was a recent reminder on China’s failure to win support.

When Hong Kong returned to Chinese sovereignty in July 1997, it did so under “One country, Two systems,” a legal commitment to a high degree of autonomy enshrined in the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984. Since the 1997 handover, this treaty formed Hong Kong’s de facto constitution, the Basic Law, China pledged to preserve many freedoms not found in the mainland itself for the duration of a 50-year transition period, till 2047. In recent years, Beijing has continuously expanded its political control at the expense of Hong Kong’s autonomy. At the same time, it intends to preserve economic freedoms that keep the city functioning as an Offshore Financial Center (OFC). China’s leadership appears to see no contradiction between keeping economic liberties in place while gradually eroding the underlying institutions.

However, the dilemmas posed by the ongoing protest movement and government responses suggest the People’s Republic of China (PRC) cannot have both full political control and a liberal economic environment. Hardline efforts to curb the political crisis are generating insecurity and damaging the long-established trust in Hong Kong’s autonomy. From a business point of view, Hong Kong’s institutional integrity and hence reliability are what counts, so the government’s response to the crisis is of primary importance.

Hong Kong’s status as a financial gateway is at risk, caught between the differing needs of China’s government and international businesses. The city might have peaked as an offshore financial center (OFC). A rapid demise of its gateway function would put major pressures on China’s global economic ambitions. But Hong Kong still occupies a vital and not easily replaceable role for China over the coming decade.

2. Hong Kong’s tested institutional arrangement provides China with the best of both worlds

Hong Kong has long occupied a crucial intermediary role for China’s economic development. Its companies were pioneer investors during China’s initial economic reforms and opening in the early 1980s, and the city then became a vital trading hub for China’s exports. Nowadays, Hong Kong is first and foremost an essential financial gateway enabling the smooth flow of capital into and out of China. Stock exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen may have overtaken Hong Kong by market capitalization size, but they primarily still serve the domestic market despite ongoing efforts for reform and opening.

At present, China lacks the institutional environment needed to establish a truly international financial center within its own borders. The CCP’s fear of ceding control of capital flows to market mechanisms has produced limited reforms to this area. This has resulted in highly selective opening measures paired with over-regulation, restrictions or lack of transparency. The main stumblings to remain are China’s lack of a fully convertible currency and strict capital controls.

On the other hand, Hong Kong’s economic liberties under its Basic Law provide a high level of legal reliability. Indispensable features for maintaining an international financial center include:

- Article 19: Independent judiciary

- Article 25: Equality before the law

- Article 27: Freedom of speech, of the press and of publication

- Article 109: Safeguarding the economic and legal environment to uphold Hong Kong's status as an international financial center

- Article 112: No foreign exchange controls and a freely convertible Hong Kong dollar

- Article 116: A customs territory separate from China

Hong Kong’s courts, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) and the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) have an international track record for safeguarding the regulatory and legal environment. These institutional elements are accompanied by a sophisticated market infrastructure and professional services experienced in dealing with both the PRC and international markets.

They include auditing and banking services, lawyers and China equity analysts. Furthermore, Hong Kong provides derivative markets such as futures (e.g.

Hang Seng Index Future and H-share Index Options) and currency hedging, which are largely underdeveloped in China but crucial for financial investors.

Hong Kong’s distinct institutional characteristics under the Special Administrative Region’s autonomous status provide a convenient workaround to the limitations of China’s institutional and economic framework that currently confront foreign and Chinese investors. It is a symbiotic relationship that ensures access to global capital while retaining a high degree of control. Hong Kong also acts as a major testing ground for experiments with policy measures geared toward gradually establishing inter-linkages with global capital markets.

2.1 Hong Kong plays a key role for China by linking on- and offshore financial markets

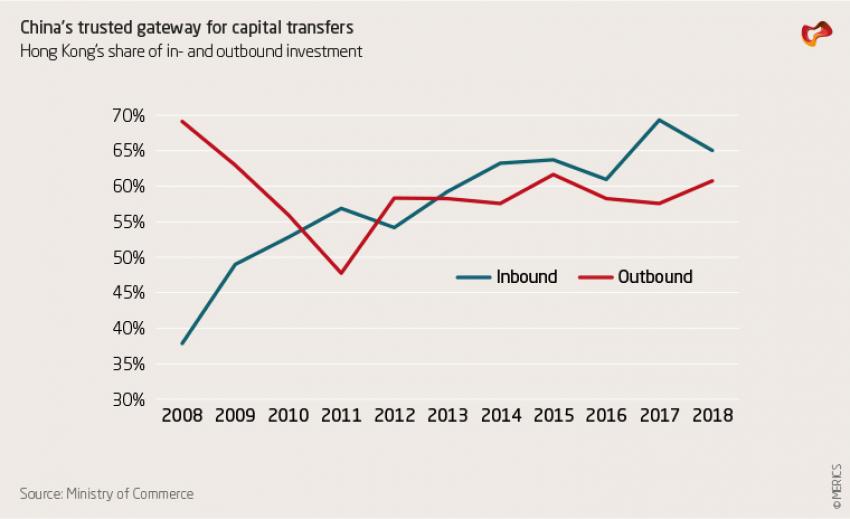

Hong Kong facilitates capital flows by providing investors with trusted channels for both foreign direct and portfolio investments, allowing them to circumvent restrictions in China. Due to its favorable institutional setting for investors, Hong Kong has secured a dominant position for itself in handling in- and outbound investment flows. In 2018, 65 percent of FDI accessed China via Hong Kong. Likewise, Chinese outbound investment in large part flows through Hong Kong’s financial system (see exhibit 2).

As the internationalization of the Chinese yuan (CNY) remains at a low level, outbound investments are mostly denominated in US dollars (USD), which China can raise more effectively in Hong Kong, due primarily to the lack of capital controls. Raising these funds offshore allows China to tap into the offshore CNY market. Foreign currency financing in Hong Kong reduces capital outflow from China. Hong Kong’s financial markets also reduce the need for China to use its foreign exchange reserves and thereby limit the volatility of the CNY’s exchange rate vis-à-vis the USD.

Similarly, Hong Kong is a key gateway for faster moving portfolio investment. Through the Hong Kong Connect mechanism first introduced in 2014, foreign investors have greater access to China’s stock and bond market. The trust in Hong Kong’s regulatory environment and safeguards for investor rights resulted in the now well-established inclusion of Chinese A-shares listed in Chinese stock markets to major international indices such as MSCI’s and FSTE’s Emerging Market Index (see exhibit 3).

2.2 Financial service sector functionality remains unscathed despite economic recession

The 2019 protests and government reactions have impacted Hong Kong’s economy, causing its first recession since the 2009 financial crisis. Hong Kong’s GDP contracted by 2.9 percent in the third quarter, leading the government to cut its 2019 GDP growth forecast to -1.3 percent in November. This is a dramatic contrast to its forecast of between 2 to 3 percent annual growth issued in May. The protests are not the only cause of Hong Kong’s slowdown. As an international trading hub, it is particularly exposed to the effects of the US-China trade conflict and an overall slump in the global economy.

However, the escalating and increasingly violent protests have sent visitor arrivals tumbling. Total visitor arrivals fell by 55.9 percent in November 2019 compared to the same month last year. Visitors from China, who account for around 80 percent of visitors to Hong Kong, contracted by 58.4 percent. The protest-related contractions have pulled down overall visitor arrivals in the first 11 months by around 10 percent. The number includes both dwindling tourism and business-related travel. Hard-hit sectors include retail, restaurants, hospitality, transportation, and business events such as trade fairs and conferences. The real estate market for both residential and office space has remained fairly stable.

So far, Hong Kong’s vital role as a financial center has been the least affected. For the second consecutive year the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX) topped the global list of IPOs. It completed a total of 160 new listings in 2019, which raised USD 37.2 billion USD, putting it ahead of both the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq. Hong Kong is clearly not easily replaced by China’s domestic financial centers, as this exceeded the combined capital raised in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges (see exhibit 4).

Major IPOs which have taken place amid the protests include Anheuser-Busch’s Asian unit in September and a heavily oversubscribed secondary listing of Alibaba in November. Alibaba raised 11.3 billion USD, making it the biggest IPO globally in 2019 and indicating the resilience of Hong Kong’s IPO market.

The impact on other financial indicators has also been relatively minor thus far, including the HKD/USD exchange rate, foreign currency reserves, interest rate, equity, exchange traded funds (ETF), fixed income and wealth management markets. Given the current global economic slowdown coupled with the insecurity surrounding Hong Kong’s political crisis, overall market reactions seem within normal volatility.

2.3 China cannot (yet) do without Hong Kong

The current robust performance of Hong Kong’s financial services accentuates the importance of the city for China. But from Beijing’s perspective the reliance on Hong Kong as a financial gateway was always an interim solution. For nearly 20 years the Chinese government has sought to develop alternative domestic mechanisms needed to tap into global financial markets. This trend is likely to continue, but for now China very much still depends on Hong Kong as a functioning OFC to strengthen its own economic needs.

Major damage to Hong Kong as an access point to international financial markets would come at an inopportune time for China. Hong Kong’s niche will become more contested. However, under present circumstances, alternative options would be far less optimal for China.

a) Shanghai and Shenzhen

China’s policy makers have long tried to transform domestic financial centers in Shanghai and Shenzhen to become internationally competitive, giving rise to equally long-running speculation about when they might overtake Hong Kong. Although their domestic role has grown, neither can match Hong Kong’s role in international finance. As failed attempts testify, simply trying to replicate an international financial center through policy experimentation within a pilot free trade zone is easier said than done.

The international financial community’s expectations were once again raised by the 2013 reforms to be enacted within Shanghai’s China Pilot Free Trade Zone. Initially, the plans envisioned far-reaching liberalization efforts including a fully convertible capital account, interest rate liberalization as well as lifting internet restrictions, to name just a few. Similar experiments were announced in 2012 for the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone which, among others, included plans to use Hong Kong’s common law for commercial disputes and provide flow-back channels for CNY raised offshore by relaxing restrictions for cross border capital flows.

China’s government has experimented with the introduction of selective relaxation of capital controls. Such channels include the Qualified Institutional Investor (QFII) and RMB Qualified Institutional Investor (RQFII) regimes, which enable foreign investors to directly invest in China’s stock markets. The mechanism was first introduced in 2002, and efforts to improve its appeal are continuing. Despite the recent adaptations, the mechanisms still come with a constraining regulatory framework and technical burdens for investors to participate.

However, any liberalization efforts can be withdrawn when deemed necessary by Beijing. The harsh reality was shown by the government’s intervention to cool a giddy stock market rally in 2015 as well as the introduction of stricter capital controls when the CNY was depreciating vis-à-vis the USD. The lack of trust in the commitment to economic liberties is paired with technical restrictions such as different due diligence standards.2 This is reflected, for instance, in the MSCI’s decision to include A-shares in its Emerging Markets Index using the Hong Kong Connect mechanism. The long-delayed inclusion would not have been possible using direct channels via QFII and RQFII regimes due to insufficient flexibility.

b) Macau

Macau is the PRC’s other Special Administrative Region, regained from Portugal in 1999. In Macau, institutional convergence and acceptance of China’s political and economic system are much more developed. Reports of the planned establishment of a CNY-denominated stock exchange in Macau have fueled speculation about the former colony perhaps taking on a greater role as an OFC.3 However, Macau’s economy is too small, and the city lacks the professional and regulatory experience that Hong Kong possesses. Furthermore, the city continues to be listed as a money-laundering jurisdiction by the United States and was long a major financing center for North Korea.4

There are other limitations: the local currency, the Macau Pataca, uses a currency board system, fixing it to the HKD. Its judicial independence is under question as Macau’s institutions have come under a higher degree of influence from China, even before 1999. Efforts to remove foreign judges participating in rulings on areas of “national security” were made in 2018.5 Their participation is one of the safeguards of judicial independence in the handover agreement with Portugal and was modeled on the UK’s arrangement regarding Hong Kong.

Fostering Macau as a major international finance center would entail major reputational and technical challenges. Macau can certainly take over some international financing activity, but the institutional barriers are too high to make it a credible alternative to Hong Kong.

c) Offshore alternatives

Singapore and London are the most notable offshore financial centers with the potential to serve as alternative hubs for China’s activities. China has expanded its financial footprint in an effort to raise capital and boost the internationalization of the CNY.6 London has the world’s largest foreign currency market and significant CNY business and experience, partly because the United Kingdom’s historic links to Hong Kong has generated financial institutions with strong infrastructure there. London handled 85 trillion CNY a day in the second quarter of 2019, equal to 43.9 percent of offshore CNY transactions between April and June, according to a joint report published in November by the City of London Corporation and People’s Bank of China.

Building on the Hong Kong Connect scheme, a similar link between the Shanghai and London stock exchanges launched in June 2019 to facilitate overseas listings, and a further scheme linking Shanghai with Frankfurt has been announced for November. However, the mechanisms remain extremely small in scope, currently limited to Global Depositary Receipts (GDR) which are traded independently of the underlying stock. More worryingly, such fledging schemes may not be immune to political brinkmanship, as recent controversy suggests. The Shanghai Stock Exchange has denied reports the scheme was being suspended in retribution for UK criticism of how the PRC has handled the Hong Kong protests.

Singapore has been a long-standing traditional rival to Hong Kong, both in the Asian financial sector and in other respects. In the area of financial services, the city state currently has a complimentary role. Hong Kong is particularly strong in equities and offshore CNY, whereas Singapore has a stronger position in fixed income and commodity trading. Singapore is likely to boost its already strong position in wealth management for PRC citizens. It may also become a more favorable destination for setting up Asia Pacific headquarters of multinationals, should companies decide to make operational changes due to the situation in Hong Kong. There is already some evidence that senior expat personnel are beginning to move their families to Singapore.

China has made diplomatic efforts to expand the role of offshore financial centers in its economy, especially in Europe. However, for China’s leaders the process has limits. It is undesirable for China’s crucial international financing needs to be within a foreign jurisdiction and vulnerable to the decisions of foreign governments. This is unappealing for any government, but it poses a particular risk to the PRC’s aspirations as a rising global power.

3. Hong Kong’s position as an offshore financial center is challenged

Hong Kong’s unique position as an international center for finance and trade is under severe pressure. The city has long prided itself on providing a business-friendly environment, and the Hong Kong government wants to maintain this image. Amid the recent anti-government protests, Carrie Lam’s administration has sought to reassure businesses and markets by referring to international rankings that still placed the city among the top financial hubs.7 Looking forward, it would be unwise to find comfort in Hong Kong’s high rankings as the political crisis has the potential to shake the very institutions that Hong Kong’s liberal economic system rests on. At present, Hong Kong remains a functional OFC, but its status must be viewed as being at risk. There are four different reasons for this judgment:

Risk 1: An escalating economic and financial crisis

Taken together, the effect of the protests on Hong Kong’s economy and financial markets has been far from crippling. For now, there is no indication of panic. Nevertheless, the risk of an economic and financial crisis remains. Without a political solution, a further escalation of violence and political instability could result a loss of investor confidence and trigger a financial crisis.

Reports of the wealth management sector moving assets from Hong Kong to Singapore reflect this risk.8 The Monetary Authority of Singapore has confirmed an uptick in inquiries at local banks to facilitate the reallocation of assets, but the actual flows are not significant.9 Hong Kong’s capital and financial account recorded a net outflow of 13.2 billion USD in the third quarter. This was considerably higher compared to the net outflow of 4.4 bn USD in the second quarter but remained within normal volatility.

Accelerated capital outflow could trigger a financial crisis that could threaten the HK dollar’s peg to the USD and shake the city’s role as an OFC. The HKMA uses a Linked Exchange Rate System (LERS) to manage its currency within a trading band of 7.75 and 7.85 HKD to the USD. In wake of a financial crisis, capital outflow would cause the HKD to weaken, forcing the HKMA to defend the currency by buying USD using Hong Kong’s foreign exchange reserves.

This scenario would reduce liquidity in the market and push up interest rates in Hong Kong in order to attract capital inflow – but with potentially detrimental effects on the local economy. Under the LERS the HKMA is required to hold at least 100 percent of the monetary base in foreign currency reserves. Currently they are at around 250 percent, which means the Hong Kong dollar peg is very solid.10 In order for the HKMA to be forced to abandon the currency’s peg to the USD the situation would need to escalate into a prolonged and substantial economic crisis.

Risk 2: Hong Kong’s special trading status rests on international recognition

US President Trump’s decision to sign the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act (HKHRDA) into law is largely symbolic in nature. However, it adds another layer to the complexity of Hong Kong’s status and carries a stern reminder of the geopolitical dimension. Among other measures, the law mandates an annual review of Hong Kong’s level of autonomy.11 Beijing is now faced with the new reality that its choices to deliberately undermine Hong Kong’s institutional framework could have consequences beyond its control.

Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy, stipulated in the Basic Law and known as “One Country, Two Systems,” requires international recognition for the city to be granted special trade status separate from China. It is at the discretion of the EU or the United States to withdraw their trust, which might have dire consequences for Hong Kong’s international position in finance and trade. Given greater tension in Sino-US relations, there is also a potential risk that the law could be used to increase diplomatic pressure on China through its reliance on Hong Kong’s financial sector, independent of actual developments in the city itself. For example, it could be used as a bargaining chip within the US-China trade negotiations. The presence of the law therefore adds to the uncertainty of Hong Kong’s international position, dimming the outlook for more long-term investment.

Risk 3: Political pressure on companies erodes Hong Kong’s economic liberties

Companies operating in Hong Kong are increasingly exposed to Chinese influence operations and political pressure. These challenges were evident prior to and separate from the recent protests: in 2011, Moody’s, the rating agency, was taken to court and fined over its “red flag” report on the financial state of some Chinese companies.12 The court case triggered concern over whether independent financial reporting was still possible. More broadly, the growing stakes of mainland entities in the ownership structures of Hong Kong press and publishing houses call into question the local media’s ability to provide independent information or criticism.

These concerns have been amplified by increasingly authoritarian corporatism during the recent protests, as in the case of Hong Kong’s flag carrier Cathay Pacific Airways. The Civil Aviation Authority of China (CAAC) threatened that all Cathy Pacific flights into or over China would be banned unless it suspended staff who had supported or participated in the protests. Cathy Pacific complied by laying off several employees even though freedom of assembly and free speech is guaranteed under Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

In a similar fashion the global ‘big four’ accounting firms KPMG, Ernst & Young, Deloitte and PricewaterhouseCoopers came under pressure over their response to the support some staff had shown for the protests. The onslaught on the ‘big four’ can be interpreted as a political signal to the business community to subordinate itself to the CCP and puts Hong Kong’s institutional independence in question

Risk 4: Beijing’s hardline measures undermine Hong Kong’s independent judiciary

Hong Kong’s judiciary has so far managed to retain its reputation for judicial independence despite legal grey areas that emerged before the recent unrest was triggered by a since-abandoned proposal to permit extradition for trial under mainland law. High profile cases stoking anxieties included the 2015 disappearance of five Hong Kong-based publishers and the forced repatriation of Chinese billionaire Xiao Jianhua in 2017. These cases underlay fears that rule of law in Hong Kong may soon belong to the past.

The political crisis is adding pressure on the judiciary’s ability to act independently. The communiqué that emerged from the CCP’s 4th Plenum in early November heightened worries that Beijing might circumvent Hong Kong’s legislature to interfere in court rulings, and more specifically that issues of interpretation of the Basic Law could be further transferred away from Hong Kong’s courts to Beijing. Its language about the need to act on the basis of “establishing a sound legal system and enforcement mechanisms for safeguarding national security” raised concerns.

Hong Kong’s judiciary faces testing times as legal cases related to the protests move through the courts, and Beijing responds. The difficulties are exemplified by legal challenges related to the Emergency Regulations Ordinance (ERO). In late November 2019, the Hong Kong High Court ruled the “mask ban” introduced under the ERO, as partially unconstitutional.13 The National Peoples’ Congress (NPC) issued a rebuttal, arguing that it alone had the power to decide the constitutionality of Hong Kong legislation – even though Hong Kong courts have ruled on constitutional matters in the decades since the 1997 handover. The NPC statement, even if it remains a verbal warning shot, threatens to erode the separation of powers, and could pave the way for growing direct interference from Beijing on issues of national security.

The colonial era ERO gives the Hong Kong Chief Executive far reaching powers in making new legislation outside of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (LegCo), which could also affect economic liberties (Articles 2 e, f, k and i). The HKMA recently felt it needed to clarify that rumors of restrictions on the financial system were unfounded.14 Either way, the government’s willingness to use the far-reaching ERO legislation risks to undermine the separation of powers and adds to the insecurities facing business.

4. Stuck between a rock and a hard place: Hong Kong’s status as an OFC is vulnerable

Despite the months-long protests, Hong Kong’s role as an OFC remains apparently solid in most respects but its ability to preserve this role is increasingly being questioned. The demonstrations have had little impact on the functionality of infrastructure and transportation and are often limited to small areas of the city, even though the level of vandalism and violence has been unusually high by Hong Kong’s standards, given its reputation for a high degree of order.

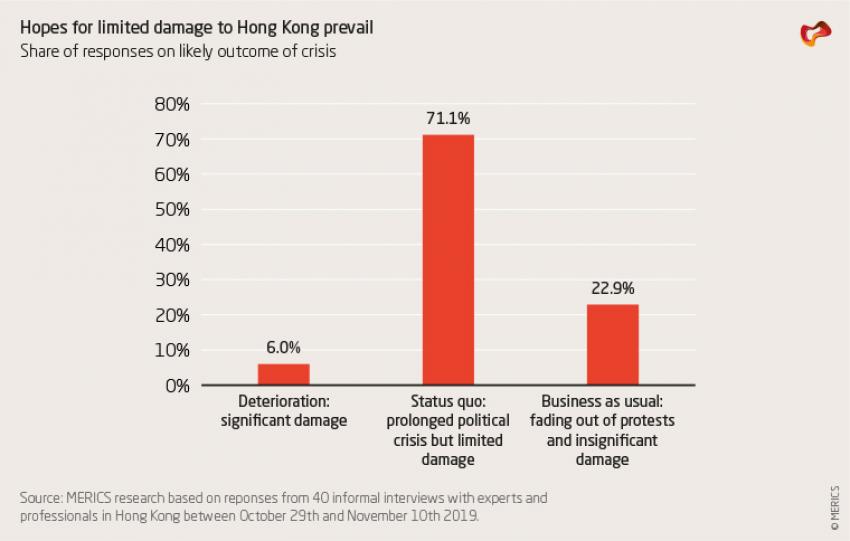

Our research trip end of October and early November 2019 was marked by relative calm, nurturing hope that the worst was over. However, the most violent protests so far, involving the siege of Hong Kong Polytechnic University kicked off on November 11. It serves as a reminder that, despite periods of relative calm, stability is no longer guaranteed. Given the volatility of the situation and the lack of any clear strategy to resolve it, it is hard to say how the crisis will play out. Below, we explore several scenarios as to how the political crisis might affect Hong Kong’s ability to function as an OFC (see also exhibit 5).

Scenario A: A deterioration in stability triggers significant damage

The rapid breakdown of Hong Kong’s OFC role could be triggered by further massive deterioration in public safety or the economy. This scenario may well see the expanded use of ERO emergency powers (i.e. restrictions on internet, information, capital flow), or even martial law and some form of intervention by the Peoples’ Liberation Army. Under these extreme conditions, it seems inconceivable that Hong Kong could still function as an OFC. The damage to Hong Kong’s institutions would be so rapid that it would deliver a significant blow to its financial service industry.

Scenario B: Protests continue, but Hong Kong remains functional

This scenario basically reflects an evolution of the status quo; regular protests including flare-ups of violent unrest coupled with increasingly forceful pressure for convergence with China. Damage to Hong Kong’s OFC role would accelerate but remain gradual. Stronger PRC influence over Hong Kong’s institutions would slowly emerge as the new reality, enabling finance and business to anticipate changes. The institutional cracks in Hong Kong’s economic autonomy would widen but no individual factor would in itself be significant enough to instantly cripple the city’s function as an OFC.

Scenario C: Protests fade out, and stability returns

The protests lose momentum, and everything returns to something like the previous normality. The most likely routes to this outcome would be 1) the Hong Kong government accedes to some of the protestors five core demands or 2) there is an intermediary but sufficiently significant solution which buys time, for instance the resignation of Carrie Lam’s government.15 It could also be result from the Hong Kong government’s “carrot and stick” approach: mixed measures of economic sweeteners and more restrictive, but not extreme, policies by the security and legal apparatus. Under this scenario Hong Kong would maintain most of its current level autonomy, and its institutions would be preserved.

5. Hong Kong’s smooth integration into China seems increasingly unlikely

Hong Kong’s convenience as an international trading and financial center with an institutional framework favorable to both China and international businesses continues to fuel hopes that its position will remain unaffected by events. But this may be wishful thinking. There is an imminent risk of setting off a spiral of further miscalculations by both sides. Beijing and the Hong Kong government, or the protest movement, may well take actions that risk triggering yet more drastic steps by the other side.

The opacity of Beijing’s positions on Hong Kong’s looming integration into China in 2047 mean the city will likely experience a prolonged period of insecurity. This will be harmful to its position as an OFC. Essentially the CCP needs Hong Kong’s economic liberties but could do without the liberal-minded people that come with it. The integration process is likely to be painful even in the more optimistic scenarios. Maintaining a balance between political and economic goals will become more challenging in a crisis-ridden environment.

It will be difficult for the PRC and Hong Kong governments to avoid tighter political control damaging Hong Kong’s stable legal environment as convergence grows nearer. The mainland’s national security and other political interests are ultimately incompatible with the protection of economic freedoms through rule of law and separation of powers. By undermining Hong Kong’s legal system in an effort to boost convergence, China has sent the clear signal that legally guaranteed rights are only safeguarded as long as they are in line with Beijing’s interests.

Without any major concessions towards the protest movement Hong Kong will most likely face a prolonged crisis, rendering its trusted institutional arrangements extremely vulnerable. China sees itself under pressure to find a response to the current crisis. Under the current circumstances, accelerated and possibly harmful changes to Hong Kong’s institutions can be expected. The CCP risks eroding the very institutional foundations necessary for an OFC it is struggling to establish within China itself. There may well be a point of no return, when Hong Kong’s status as a rule of law jurisdiction is no longer deemed credible. Absent of any credible alternatives the premature demise of Hong Kong’s gateway function would be costly for China while European businesses will need to brace themselves for losing the institutional convenience Hong Kong provides.

The authors would like to thank MERICS staff Katja Drinhausen and Mareike Ohlberg for their helpful input for this paper.

- Endnotes

-

1| Commonly referred to “extradition law”, but officially the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019.

2| Hong Kong uses the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) standard as opposed to the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII) standard used in China.

3| Macau Daily Times (2019), "The Nasdaq of China - Macau submits application to set up stock exchange: report". https://macaudailytimes.com.mo/the-nasdaq-of-china-macau-sub-mits-application-to-set-up-stock-exchange-report.html. Accessed November 18, 2019.

4| United States Department of State (2019), "International Narcotics Control Strategy Report Volume II Money Laundering." https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/INCSR-Vol-INCSR-Vol.-2-pdf. Accessed November 30, 2019.

5| United States Department of State (2019), "International Narcotics Control Strategy Report Volume II Money Laundering." https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/INCSR-Vol-INCSR-Vol.-2-pdf. Accessed November 30, 2019.

6| See Maximilian Kärnfelt, China's currency push. The Chinese Yuan expands its footprint in Europe, Berlin: MERICS, 2019. https://www.merics.org/en/china-monitor/chinas-currency-push. Accessed November 15, 2019.

7| For example, the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World report or the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index.

8| Channel News Asia (2019), "Wealth managers head to Singapore as China concerns dim Hong Kong's lure." https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/wealth-managers-choose-singapore-over-hong-kong-china-11676124. Accessed November 15, 2019.

9| SCMP (2019), "Singapore sees small inflows of capital amid Hong Kong unrest, says central bank." https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3034337/singapore-slow-down-shows-signs-nearing-end-central-bank. Accessed November 15, 2019.

10| Hong Kong Monetary Authority in BIS Papers No 73 (2013), "Monetary operations under the Currency Board system: the experience of Hong Kong." https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap73j.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2019.

11| Article 151 of its Basic Law states: Hong Kong can, independently from the mainland, “maintain and develop relations and conclude and implement agreements with foreign states and regions and relevant international organizations in the appropriate fields, including the economic, trade, financial and monetary, shipping, communications, tourism, cultural and sports fields.”

12| Securities and Futures Commission (2016), Press release "SFAT affirms SFC decision to reprimand and fine Moody’s over Red Flags Report." https://www.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/gateway/EN/news-and-announcements/news/%20doc?refNo=16PR34. Accessed November 18, 2019.

13| The enforcement of “mask ban” was halted December 10th 2019 by the Court of Appeal until the government’s appeal against the High Court’s ruling is concluded.

14| The Government of Hong Kong (2019), Press release "Government clarifies rumours about Emergency Regulations Ordinance". https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201910/06/P2019100600858.htm. Accessed November 13, 2019.

15| For more information on background of the protests see Benjamin Haas, Mareike Ohlberg, Claudia Wessling (2019), "Standoff in Hong Kong: a domestic crisis affecting international actors". https://www.merics.org/en/standoff-in-hong-kong. Accessed November 21, 2019.

-